The painting Hell Here Now shows the Turkish landscape at Gallipoli occupied by ANZAC troops in 1915. The painting includes quotes from the Gallipoli diary of Alfred Cameron, which is held in the Turnbull Library, and a quote from a Turkish solider Ismail Haaki. Like many young men Alfred Cameron could not wait to get away to war. His only worry was that the show would be over before he got there.

Alfred Cameron was working on his uncle’s farm at Culverden in North Canterbury when war was declared. He began his daily diary on the 13th August 1914 with the words, ‘Enlisted for first New Zealand Expeditionary Force to European War.’

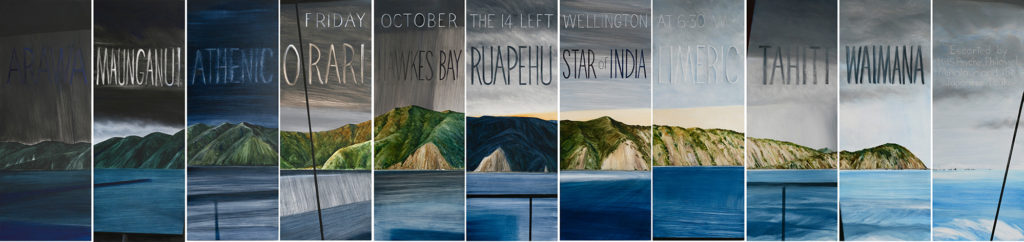

On the 16th of October ten troop transports and their naval escorts steamed out of Wellington Harbour past a landscape that looked strangely like Gallipoli. Alfred Cameron was on board the Tahiti.

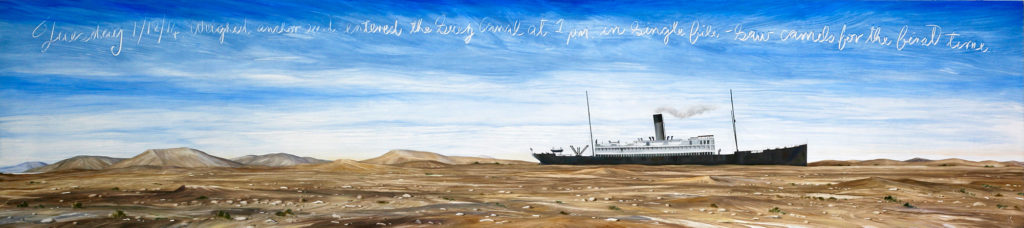

On the first of December Cameron sailed through the Suez Canal. He wrote in his diary about seeing camels for the first time.

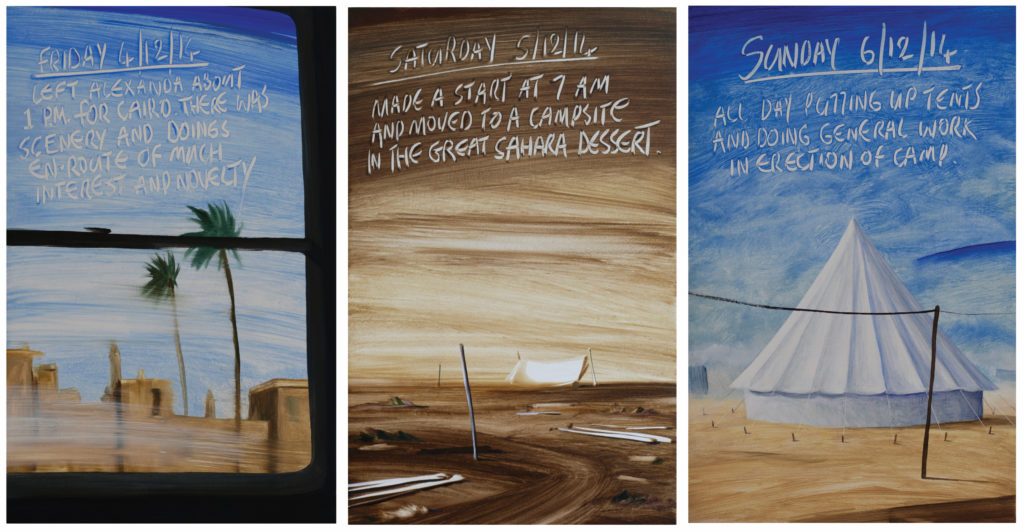

The New Zealand troops disembarked at Alexandria and moved to a camp in the desert near Cairo.

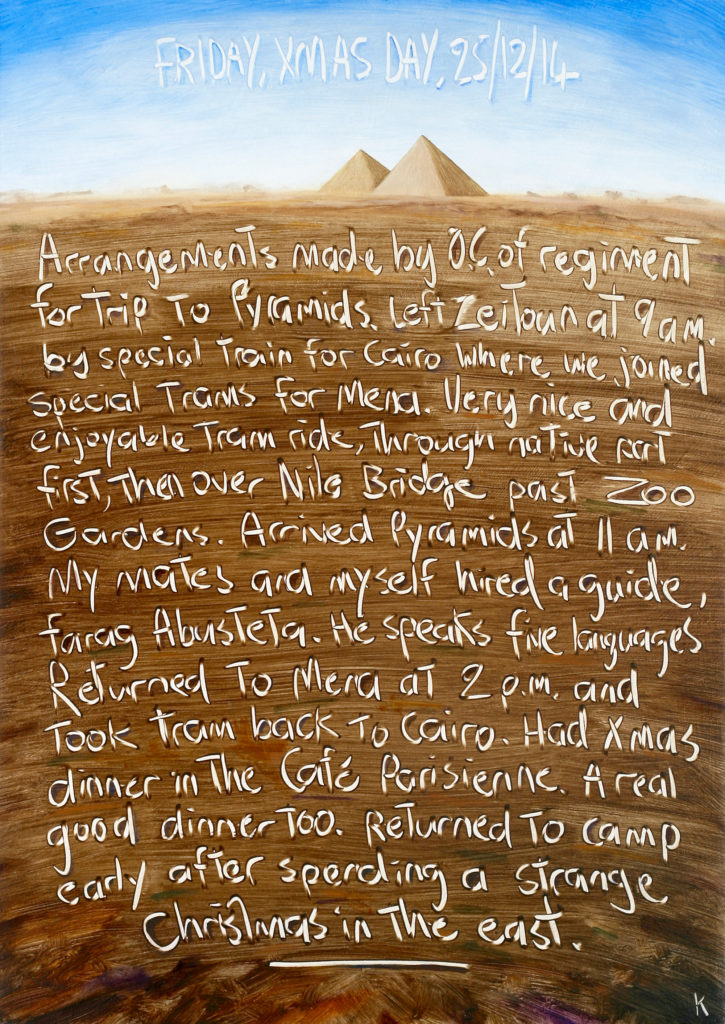

On Christmas day 1914 Cameron described a trip to the Pyramids.

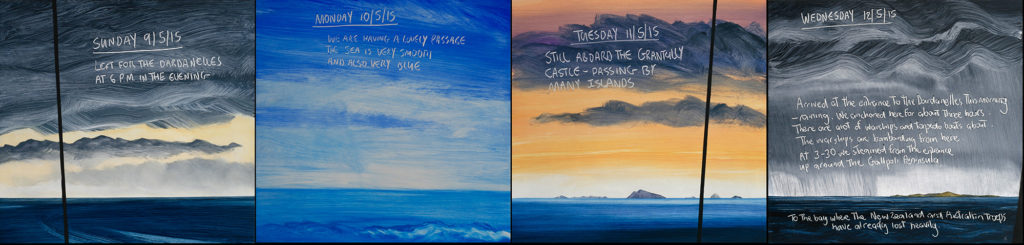

In early May Cameron writes, ‘Great news, off to the Dardanelles on Sunday.’ This was a four-day journey on the steam ship Grantully Castle.

Cameron kept his diary for three weeks on Gallipoli. The last words he wrote at the end of May were, ‘Dam the place no good writing any more.’

In July Alfred Cameron was wounded and evacuated to a hospital in Cairo. He returned to New Zealand and became a farmer near Cricklewood in South Canterbury.

When I was working on this show Slava Fainitski from Orchestra Wellington had the next door studio. He suggested a musical interpretation of the paintings so we got together with Catherine Mckay on piano, and Brenton Veitch on the Cello, Slava on violin and with Robin Kerr reading from Cameron’s diary performed at Pataka over ANZAC weekend.

This performance featured Alfred Hill’s recently rediscovered Trio in A Minor to show the imperial optimism of the New Zealand that Alfred Cameron was leaving and the sombre Faure Elegy representing Cameron’s despair at the loss of his friends in what the historian Chris Pugsley called, ‘the stark reality of a group of amateur citizen soldiers facing wars reality for the first time. And there was nothing glorious about it. It was mistake, blunder, muddle, death and disease.’

You can listen to an interview by Ava Radich on the Concert Programme with Bob Kerr and pianist Catherine Mckay about this visual and musical collaboration here.

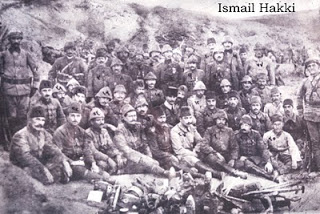

The quotation along the top of the painting Hell Here Now is from the Turkish officer Ismail Hakki, expressing his anger at being made to “kill each other without reason”.

Here, Bulent Atalay, the grandson of Ismail Hakki, writes about his grandfather.

I have been through the Gallipoli Straits by the sea, as well as on both storied shores many times. Most memorable to me is a visit in 1967, when my new bride and I, accompanied by my mother and father, drove down the Gallipoli Peninsula from Istanbul. It was on our lengthy drive that my father, General Kemal Atalay, then the Undersecretary of Defense for Turkey, first told us the story of his own father, and the family’s connection to Atatürk, né Mustafa Kemal (there were no last names in Turkey until 1934, when Atatürk introduced legislation for everyone to generate family names).

My grandfather, Ismail Hakki, was born in Thessalonica in the same year (1881) and on the same street where Atatürk was born. They were childhood buddies, and they fought together in the trenches of Gallipoli during eight months of 1915. A photograph was taken of my grandfather’s battalion during a break in the action. Immediately after the cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of the ANZACS, my grandfather briefly traveled to Edirne (Roman Adrionople) on assignment, and while there, on January 1, 1916, had a photograph taken of himself. He inscribed on the back of the photograph, “To my dear aunt, I survived eight months of action in Gallipoli. I will soon leave for the Eastern Front, there to face the Arabs and their “recalcitrant English leader” (Lawrence of Arabia).

Just before leaving for the Eastern Front, he briefly visited the small town of Biga, located to the east of Çanakkale and Troy, there to see his young family, ensconced in the town since shortly before the war began. There were his wife and three young children, two years apart in age – the oldest, a daughter; the middle, a son; and the youngest, another son — my father, “Mustafa Kemal”— named after Ismail Hakki’s childhood friend, and in accord with his friend’s wishes. He died in action in 1916.

A few years after the cessation of hostilities, after the founding of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923, and the election of Atatürk as the first President of the nation, an aide showed up with a letter, “We received a plea from the mothers of Australian and New Zealanders killed in Gallipoli. They are asking for permission to visit the graves of their sons.”

Atatürk muses, “What do I tell these people?” The aide responds, “Tell them, as you would any foreigner who makes an incursion into our land, ‘we will break off their legs!’”

Ataturk, smiling to his aide, responds, “I can’t do that.” He sits down and composes his own message for the families of the fallen Aussies and Kiwis:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours… You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.” — Kemal Atatürk

Atatürk’s poignant message is inscribed in the Turkish Monument to the Unknown Soldier in Gallipoli, and it is inscribed on the Atatürk Memorial in Wellington. It is no wonder that in New Zealand, there is still a sense of kinship for Atatürk and the Turks — one time enemies, but fellow witnesses to the unspeakable horrors of trench warfare — and, conversely, a resentment of the British politicians who sent a generation of their young men to fight and die in a land half-a-world away. For the Turks, the New Zealanders and the Australians, Gallipoli would forever be regarded as the moment when they gained their national identities.

By Bulent Atalay, PhD, Professor of Physics.

I AM WRITING THIS IN A CREEK WELL SHELTERED FROM SHRAPNEL

The Gallipoli diary of Alfred Cameron

Alfred Cameron begins his Gallipoli diary with the words, ‘I write these lines hoping they will be useful to those at home.’ They are in fountain pen in an elegant, formal script. The diary ends nine months later with these words scrawled across the page in pencil. ‘It’s just hell here now. No water or tucker, seven out of thirty three in number one troop on duty, rest either dead or wounded, damn the place. No good writing any more.’

When the declaration of war was read out to a crowd of 15,000 on the steps of Parliament on the 5th of August 1914 “cheer after cheer followed.” That evening, 20,000 Wellintonians marched in militaristic columns up to six deep through the streets waving union jacks and singing ‘God save the King.’

Alfred Cameron, like most young men of his generation, was swept up in this wave of patriotic fervour. Eager to get away to war Alfred, who had been working on his uncle’s farm at Culverden in North Canterbury, took his horse Percy and went into camp at Addington Show grounds in Christchurch on the 20th of August 1914. To join the Mounted Rifles a volunteer had to come equipped with a horse and saddle. At the end of September he sailed for Wellington where the they, ‘…were camped at Lyall Bay at which we all enjoyed ourselves until Wednesday the 14th of October when we all embarked again.’

Two days later on the 16th. of October 1914, on a grey, windy Wellington morning a line of troop transports and their naval escorts steamed out of Wellington Harbour. Alfred Cameron was on board the Tahiti with 600 men, 30 officers and 282 horses. Very few of the men on board knew for sure where they were going. It was simply enough to be off on their great imperial adventure. Most assumed it would be England for more training and then France and that the show better not be over before they got there.

As the convoy was steaming between Hobart and Albany in Western Australia he records, ‘Lost our first horse to septicaemia.’ The following day he records the first soldier to die, ‘Burial at sea. Corp. Gilchrist off the Ruapehu. At 3.45 pm. Ship pulled out into middle of squadron. All ships stopped engines and men stood to attention. We haven’t any brass band aboard but a pipe band is attached to 1st Infantry regiment and they played the lament.’ and then as they are refuelling in Albany he notes, ‘Second Horse died.’

The monotony of the six-week voyage was suddenly broken nine days out of Albany as the convoy crossed the Indian Ocean. Alfred recorded the excitement. ‘HMAS Sydney left us at early morning and at midday we got news by wireless to say that she had engaged the German cruiser Emden at Cocos Island, 60 miles off our route, and that the Emden had beached to avoid sinking. Sydney in pursuit of her collier. Sydney’s casualties 2 killed and 15 wounded. Emden, 200 killed and 40 odd wounded. Great enthusiasm on board us when news was made known.’

After stopping in Aden at the entrance to the Red Sea that they were told they were only going as far as Egypt. They reached the Suez Canal on the 1st. of December 1914. ‘Weighed anchor and entered Suez Canal at 1 pm in single file. Saw camels for first time. Every little way along canal we struck small camps and fortresses manned by British and Indian troops. Yesterday had identity discs or ‘cold meat medals’ issued to hang around neck, name regiment, number and religion on them.’

The New Zealanders were camped ‘in the great Sahara Desert’ at Zeitoun near the modern Cairo suburb of Heliopolis. On Sunday the 12th of December he writes, ‘all day putting up tents and horse lines and doing general work in execution of camp… The whole of the NZEF is camped here, also 200 men from Ceylon. There is also a large camp of English Tommies alongside us, about 8000 men mostly from Lancashire. Their accent is very pronounced…’

The diary records his growing friendship with George Ilsley. ‘Went into Heliopolis with G Ilsley and two Tommies. Had a look around. Went into skating rink at Luna Park. Large rink with good wooden floor.’ Something of the excitement of a Canterbury farm worker who would never have had the opportunity to see the world were it not for the war, is conveyed in his description of Christmas Day 1914 ‘… Arrangements made by OC of regiment for trip to pyramids. Left Zeitoun at 9 am. by special train to Cairo where we joined special trams for Mena. Very nice and enjoyable tram ride through native part first and then over Nile Bridge and past Zoo Gardens. Beautiful tarred road all the way with trees along each side, arrived pyramids at 11 am and had lunch in the Mena refreshment rooms. My mates and I hired a guide at 5 piastres each. An Algerian named Farag Abustetah. He speaks five languages.’ Farag must have been an engaging guide, the next three pages are filled with historical detail about how King Cheops took 30 years to build his tomb, ‘but owing to his having treated his native workers badly, beating and starving them, on his death they threw him into the sea’. The Christmas day entry finishes with. ‘Then took tram back to Cairo and had dinner at the Café Parisienne, a real good dinner too. Returned to camp early after spending a strange Christmas in the east.’

The routine of training and desert marches ground on until Easter when the boredom boiled over into a Good Friday riot in the brothel area of Cairo, Alfred reported. ‘Exercised the horses in the morning. Usual holiday in the afternoon. No leave for Cairo owing to a big fight in the Bull Ring last night. The red caps, (Military Police) using no tact, fired on Australians and New Zealanders. One Australian reported killed and several New Zealanders and Australians wounded. This has caused our men to lose control of themselves. Several of the Red Caps have been caught and thrashed and boys have threatened to shoot all the red caps they lay their hands on.’

The landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula were the idea of the first Sea Lord of the British Admiralty, Winston Churchill. The object was to capture the Dardanelles Straits, steam through to the Turkish capital, Constantinople and force the Turkish Government into submission.

Alfred Cameron was not in the first troops that landed at Gallipoli on the 25th of April, the day we now commemorate as ANZAC day. He did not land until the 12th of May when the Mounted Rifles had to leave their horses behind and fight as foot soldiers. His diary entry for the 25th of April, records a quiet day, ‘Usual Sunday proceedings. Orderly trumpeter till evening. Went for a quiet walk after tea.’ It is not until one week later that there is the first hint of news from Gallipoli, ‘Sunday afternoon a few of us went to the garden fete in the Esbeckia Gardens, a very enjoyable time. Pictures in the evening. Heard of great casualties among the Australian and NZ troops.’ Despite the great casualties, four days later he is elated to write, ‘Great news, off to the Dardanelles on Sunday. All very excited.’

His diary entry for the 12th of May 1915 reads, ‘Arrived at the entrance to the Dardanelles this morning, raining. We anchored here for about three hours. There were a lot of warships and torpedo boats about. The warships were bombarding from here. At 3.30pm. we steamed from the entrance up around the Gallipoli Peninsula to the bay where the NZ and Australian troops have already lost heavily. We disembarked quickly and after a two-mile steam on a torpedo boat we got ashore safely although were under shellfire all the way. We went straight up a bushy gully for shelter. Here we stopped the night in dugouts. Could not sleep owing to the continuous rifle fire going on just above us.’

Alfred recorded the large Turkish attack of the 19th May, ‘Last night we went to bed fully dressed and at 12.30 am. Were called to arms as the enemy were attacking strongly. The rifle fire was deafening until daylight when the batteries started work… Just now George Ilsley and myself are with the machine gun, which is firing on 500 Turks in some scrub…We are in a very tight corner as they have far superior numbers to us. Yesterday the enemy gave us 24 hours to surrender but there is no give in for us. …I am writing this in a creek well sheltered from shrapnel. Just in front of me are two graves.’

On the 24th of May he recorded the armistice arranged between both sides to allow the burying of the dead, ‘The bodies have been lying a long while and are beginning to smell dreadfully. No shot has been heard all morning and the quietness seems uncanny.’

The following day there was drama at sea, ‘Quite a sensation was caused today by the sinking of the HMS Triumph by an enemy submarine. The sinking of the Triumph was witnessed by most of the troops. We noticed an explosion aboard about 12pm. midday. A minute or two later she began to list heavily and destroyers began to rescue the sailors. At ten past 12 the Triumph was sinking fast and the sailors were ordered to dive overboard. At 12.15 the warship suddenly toppled completely over and remained keel uppermost for 15 minutes when the large vessel gave a dive and disappeared. The sight was wonderful and yet pitiful’. Then in a rare departure from just reporting the facts he states, ‘The troops are not downhearted, we are waiting for their next attack when we will give them a smasher.’

As the days get hotter, the fighting more desperate and the dysentery and disease more rampant his belief that they will ‘give them a smasher’ is replaced by the reality of the military stalemate.

Thursday the 28th May, ‘…marched off towards the beach where we were told we were going to take the Turks trenches near number two outpost. We crawled and broke through bushes until midnight, all the time being fired on by enemy snipers. At twelve thirty we opened fire at the Turkish trenches, then the word ‘charge’ was given …the enemy fled and we occupied the trenches.’

Monday the 31st May, ‘ Going forward again tonight. We miss our cobbers.’ Then the despairing entry in early June, ‘It’s just hell here now, no water or tucker, only seven out of thirty three in number one troop on duty, rest either dead or wounded. Dam the place, no good writing any more.’

He did not write any more regular entries. Only a note that, ‘My cobber George Ilsley dead. Killed August 17th. Bullet through head. Buried Taylor’s Hollow.’ and, in a faint, wavering hand, on the final page of the diary, ‘August 24th. Government School Hospital, Port Said. 21 today. Received cable from home.’

He remained at Gallipoli until some time in July engaged in what had became a desperate activity for both sides, tunnelling under one another’s trenches to plant explosives. Alfred and a team of tunnellers had reached the Turkish trench when the Turks blew up the end of the tunnel. An attack by the New Zealanders held off the Turks until the wounded team of tunnelers had been dug out and carried back to their own trenches. He was evacuated to hospital in Egypt and then returned to New Zealand where he married and became a farmer in South Canterbury. The last New Zealand troops slipped away from Anzac Cove in the early hours of the 20th of December without the Turkish forces realizing they were leaving.