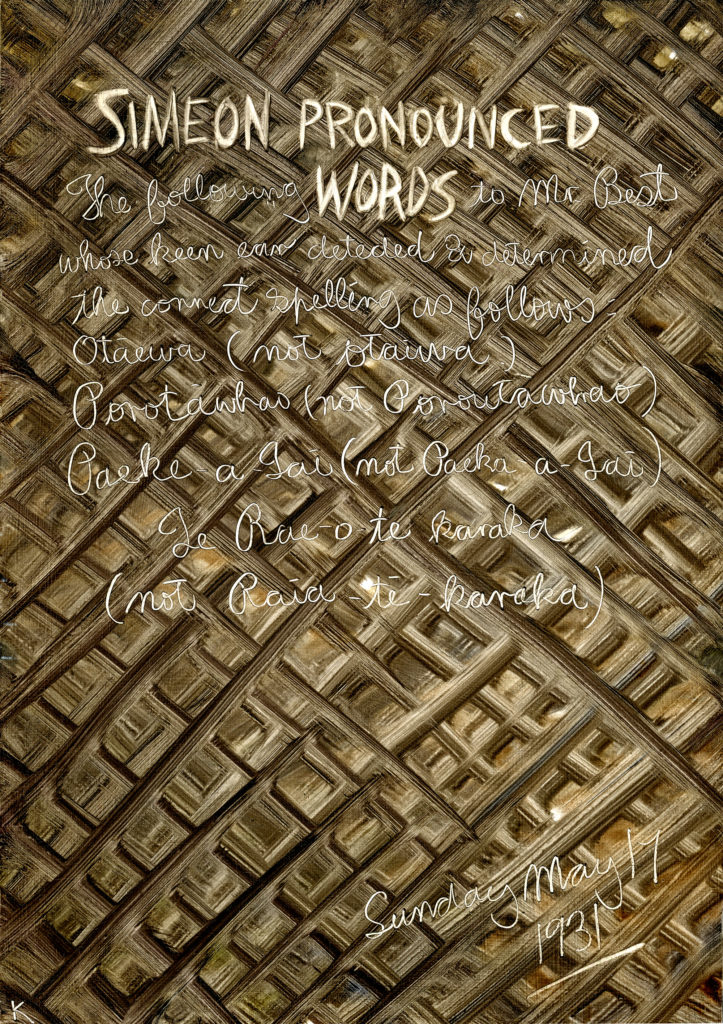

Leslie Adkin (1888-1964) was a Levin farmer, one of those extraordinary New Zealanders who, self-taught and operating outside professional academic structures, made major contributions in an enormous range of activities. As an historian, geologist and anthropologist, his views continue to stimulate and challenge; as a keen tramper, he mapped large areas of the Tararuas; and he was one of the finest photographers New Zealand has seen.

My interest in Leslie Adkin was sparked by the book An Eye for Country: the life and work of Leslie Adkin by Anthony Dreaver.

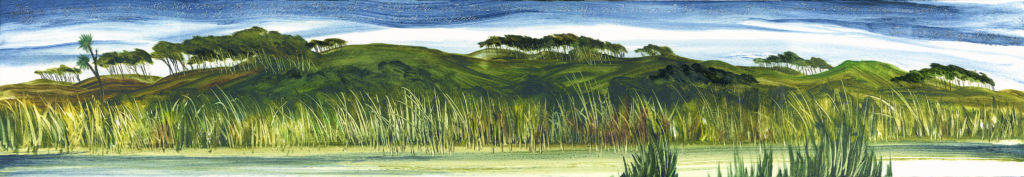

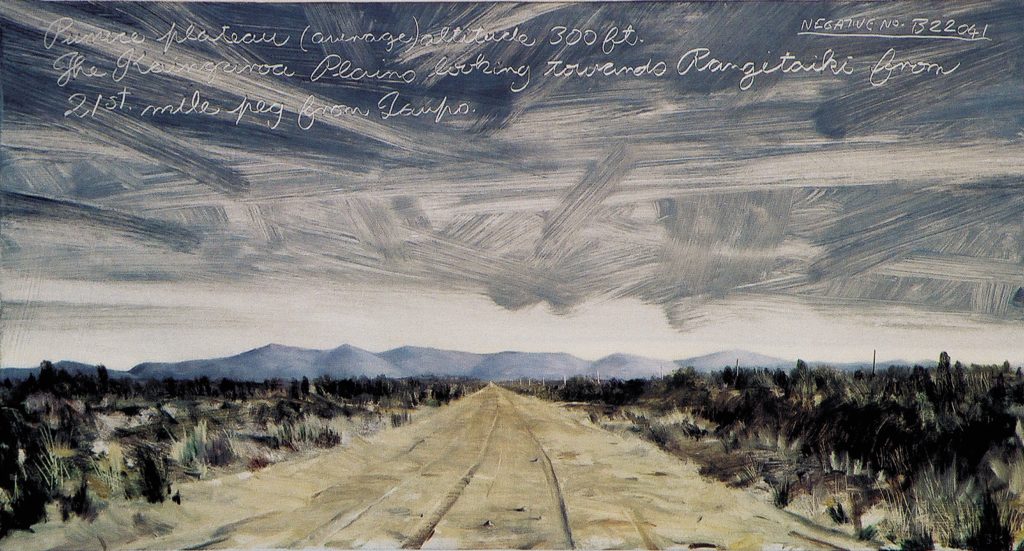

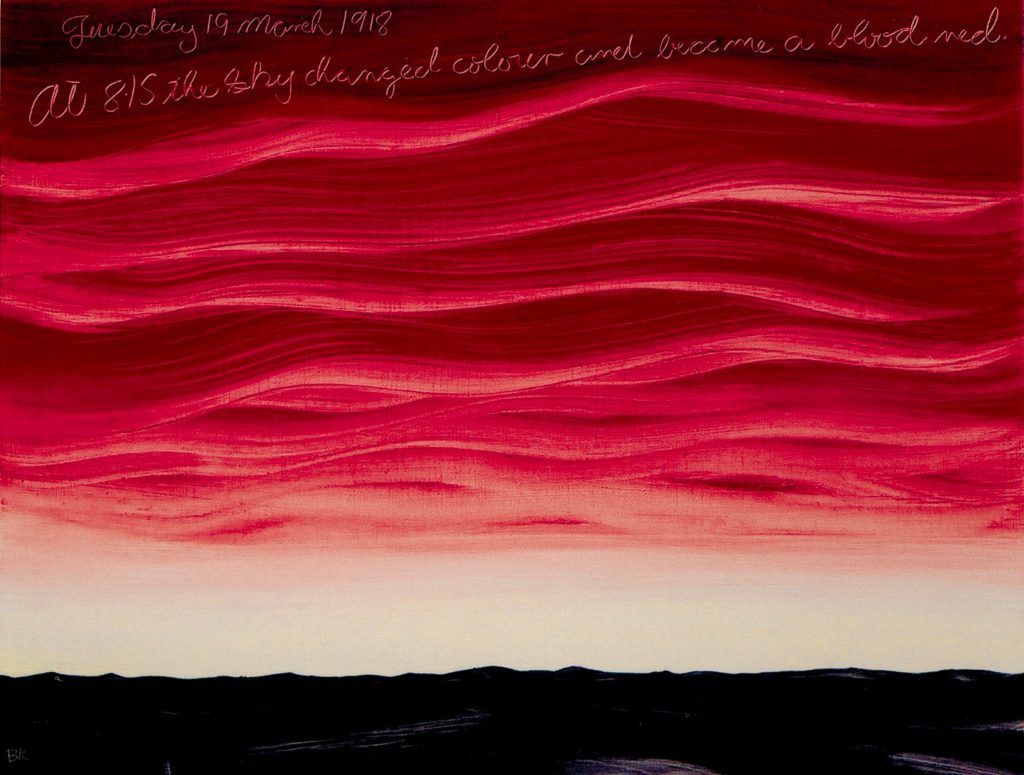

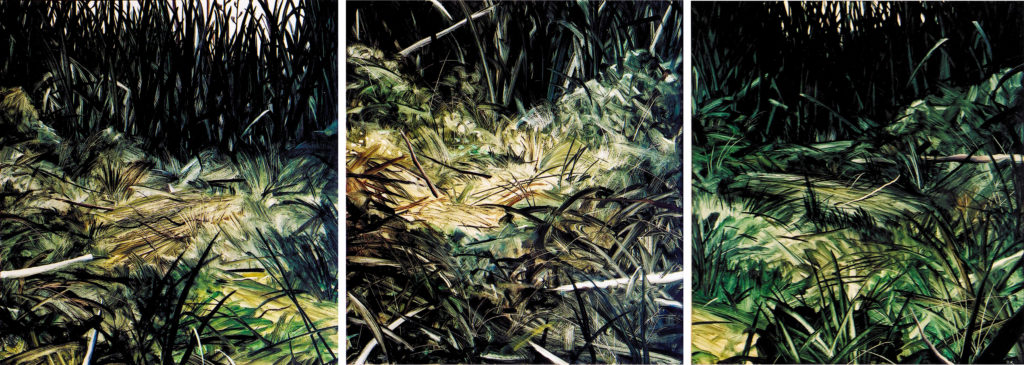

Here is a selection of paintings from Some of The Field Evidence.

These paintings were first exhibited at Idiom Gallery in Wellington and then at the Manawatu Art Gallery during August and September 2001.

The Colonial paradox – A catalogue essay by David Young

THE HOROWHENUA coast is one of those bits of country that have yet to engage the popular imagination. Its black sands, concentrations of driftwood, dumpy waves and variable fishing mean that it is definitely not resort territory. On the contrary, it tends to have attracted many who cannot afford to live elsewhere. It is a region where the westerly tends to blow more often than not and it is a sandscape that for most of European occupation here has been regarded as a kind of wasteland.

Among those with the axeman’s ‘sap on their hands’ was the farming family Leslie Adkin was born into in 1889. He too became a ‘matchbox farmer, an incendiary destroyer of nature. But, gifted with a remarkable curiosity about the land that had nurtured him and a synthesising intelligence, he grew to become an outstanding contributor to a range of connecting fields. As a struggling farmer, these were all carried out in the finest traditions of that now almost lost calling, ‘the amateur’ until in 1944 he was appointed to the Geological Survey.

His insights into the formation of the Horowhenua coast, with what are now recognised as one of the most dynamic and extensive dune systems in the world with its amazing history of ecosystems and Māori occupation, produced a wealth of learned papers.

It is all this work done in coming to understand the land he lived in that has attracted and inspired Bob Kerr in this series of paintings. Adkin’s manuscripts in his no-nonsense clear hand provide the texts. This is not to say that Bob always finds Adkin the man entirely admirable. For example Adkin’s lifelong tough individualism was sufficiently extreme to see him gladly enrolled as a special constable in the 1913 strike. For someone like Bob, who earlier in life worked as a trade union official, there is nothing special about a special constable.

But Adkin’s extensive manuscripts, to say nothing of his actual books, have come to provide pathways into the mind of a man who wrestled with many of the big questions. At the heart of Bob Kerr’s paintings is a recognition of the colonial paradox: destruction and conservation, plunder and appropriation, awe and arrogance. “I think what appeals about this bloke Adkin,” says Bob Kerr,“is that, despite himself, he tried to come to terms with the land he lived on and the history of its inhabitants. And, at the end of his life he was a conservationist.”

Sometimes Bob also draws on Adkin’s photographs, as in the Lake Horowhenua scenes. Sometimes the words alone are sufficient to inspire when Bob ‘gets’ this landscape that so few artists have bothered with.

I personally love the long lines of lively sky, the textures of old man flax fretting together, the billowing dunes, sometimes fastened down by foliage, sometimes not. Always there is the turbulence of this coast, the sense of the unexpected, and the light that catches at joggling marram.

The work is rarely “just representational, it shares with Adkin the great sense of loss arising from the Raetihi fires, his wonder at an eclipse. Other times there is quiet judgement on the elder’s views. Whether it’s in friction or in harmony, the energy between these two so different men has produced another, significant illumination of a wildly beautiful bit of country not merely forgotten, but for most, barely even apprehended.

David Young

David Young is a professional writer in the field of history and the environment – for film, print media and oral history. He is published widely in essays, articles, magazines and books.