At daybreak on Sunday 21 February 1864 Colonel Marmaduke Nixon led an attack on the undefended settlement of Rangiaowhia. The thatch of a whare in which villagers had sheltered was set alight. An unarmed elderly man came out with a white blanket raised above his head. He was killed by a hail of bullets. Two more Māori attempting to escape from the fire met the same fate. Twelve Māori were killed, including women, children and the elderly. Five members of the British force died.

I also arrived at Rangiaowhia on a Sunday morning. I wanted to paint it as it looks now. Where the whare stood is much like any other rural Waikato intersection. A blue road sign points to Kihikihi 4 kms away and to Te Awamutu 6 kms in the other direction. There are power poles, Give Way signs and a white wooden crash barrier. Neatly clipped hedges mark out phosphate green paddocks dotted with English trees. Nearby is the Rangiaowhia War Memorial Domain commemorating the First World War, The Second World War, The Korean War and the Vietnam War. Recently a plaque has been added to acknowledge the invasion of the Waikato by the British army and the deaths in the paddock next door.

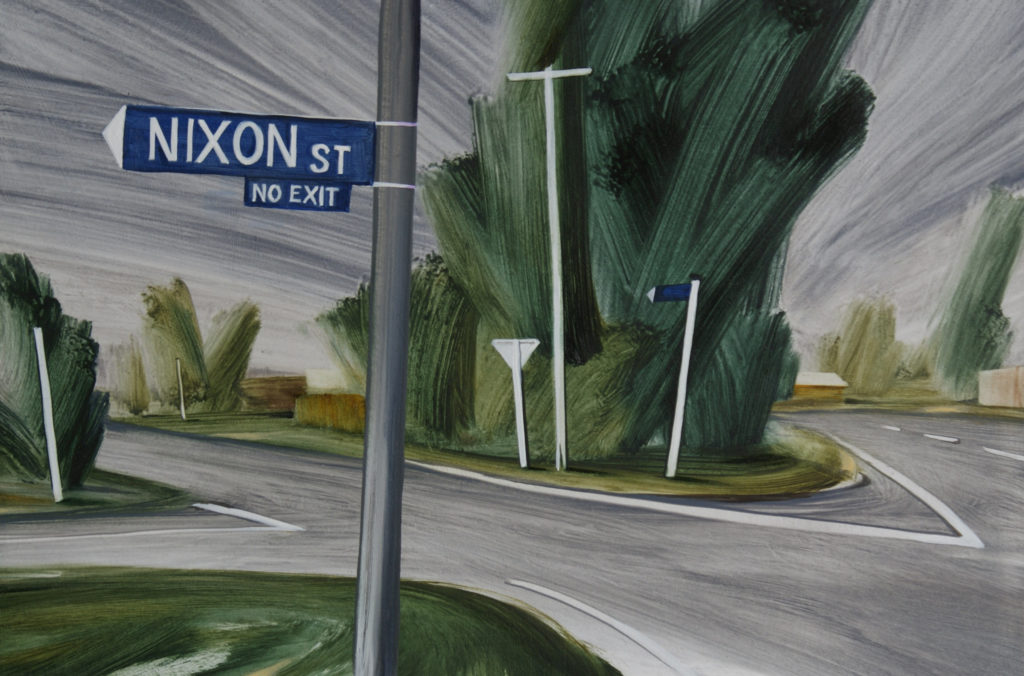

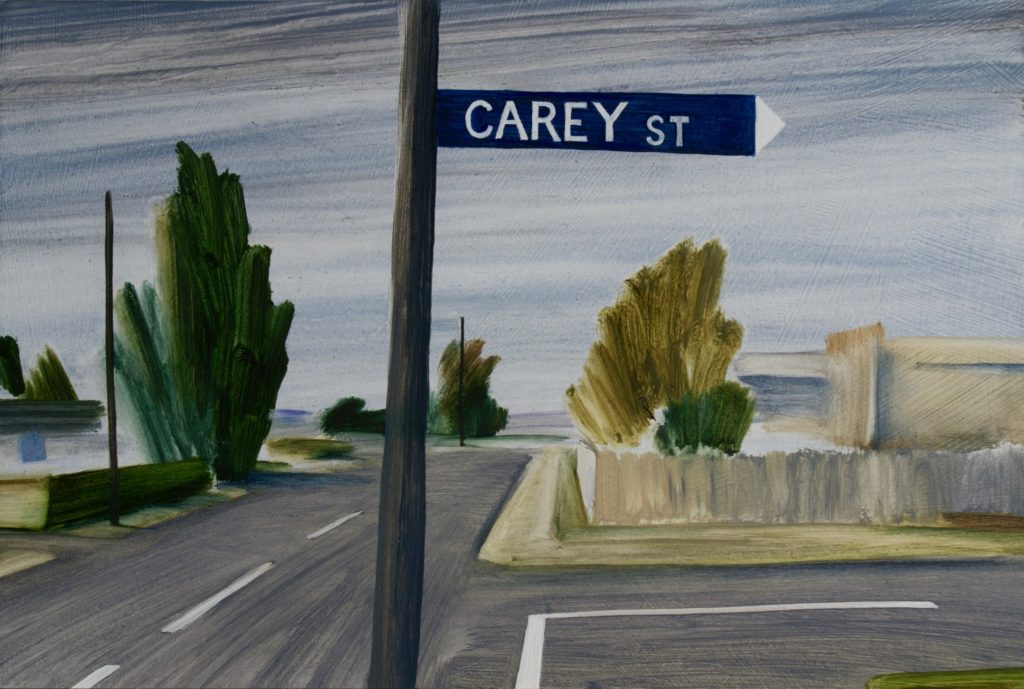

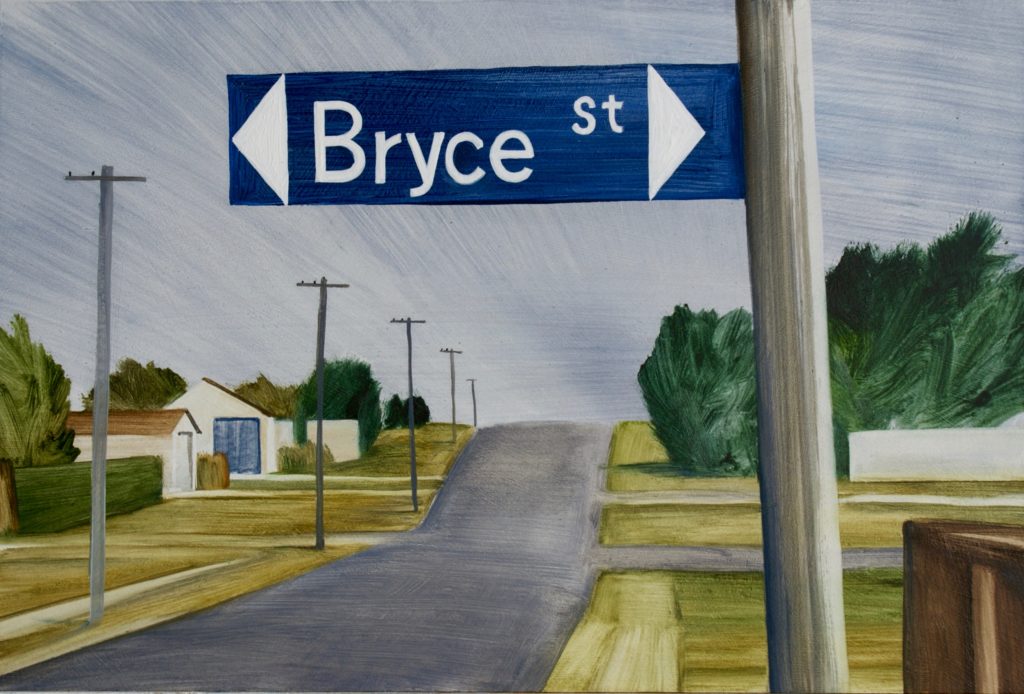

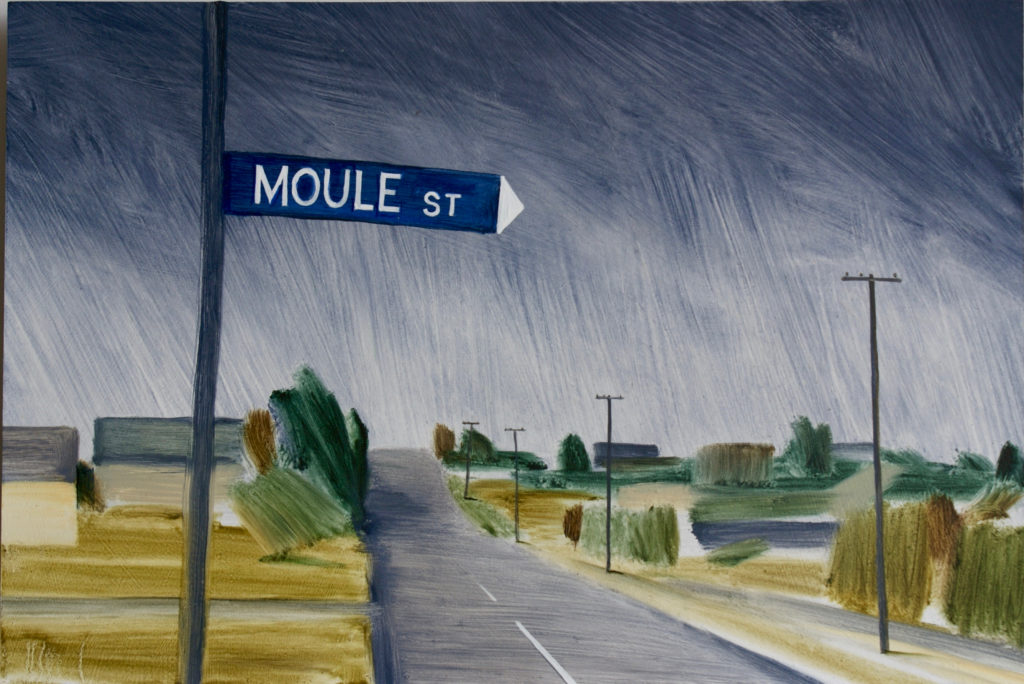

I drive into Kihkihi for a coffee along Moule Street, named after Lt. Colonel William Moule, and turn right into Galloway Street named after General Galloway. Just about every street in Kihikihi is named after a soldier from the invading army including Nixon Street.

I learnt about the incident at Handley’s woolshed from historian Vincent O’Malley’s report on the street names of Hamilton. The incident at Handley’s woolshed took place at Nukumaru near Whanganui during the campaign that colonial forces fought against the South Taranaki leader Riwha Tītokowaru. I pack the sketchbook and set off to see what it looks like now.

Just before Nukumaru I stop in the small town of Maxwell. An imposing war memorial dominates the town. I open the cast iron gate and walk up the hill to have a look. There is no mention of the war that took place in sight of the memorial. In the winter of 1868 Tītokowaru led a campaign of resistance against the confiscation of Māori land. Despite being heavily outnumbered Tītokowaru and his supporters won several victories pushing towards Whanganui.

At the intersection of Nukumaru Station Road and the highway there is a sign saying, ‘watch out for children’. I drive down Nukumaru Station Road and meet a farmer on a quad bike who points out where the woolshed would have been a little way up the railway line next to one of the dune lakes that mark the edge of the coastal sandhills. I climb up the sandhills and look down. This would have been the view that Sergeant George Maxwell and the Kai Iwi Cavalry had when they rode their horses over the brow of the hill and saw what they called a party of Hauhaus. They charged down the sandhills and attacked.

This is how Vincent O’Malley describes the attack:

‘The official report of what followed singled out Sergeant George Maxwell for praise, noting that he had ‘himself sabred two and shot one of the enemy’. The report omitted one critical detail: the Māori party that the Kai Iwi Cavalry had attacked was not a party of adult Pai Mārire fighters but a group of young children, between 6 and 12 years of age, who were out hunting pigs. One boy, aged about 10, was killed by a single stroke from a sword that decapitated him. Another boy, around 12 years old, died as a result of multiple sword attacks.’

There is no memorial to the incident at Handley’s woolshed and no explanation of how Maxwell got its name. The 2003 deed of settlement between the Crown and Ngā Rauru states that the Wanganui District Council should enter discussions with the Iwi Authority in relation to the name of the town of Maxwell. Many would like the name to revert to the older name of Pakaraka. If I was living in Maxwell I’d prefer “the Pa where the Karaka trees grew” rather than a name memorialising a child killer.

Ruapekapeka was the site of the last battle of the Northern War. The Pā was designed to counter the cannons of the British forces and it has remained relatively intact because of its location and terrain and because for much of the time since the battle in December 1845 it has been a reserve.

These paintings were first shown at Whitespace Gallery in 2020