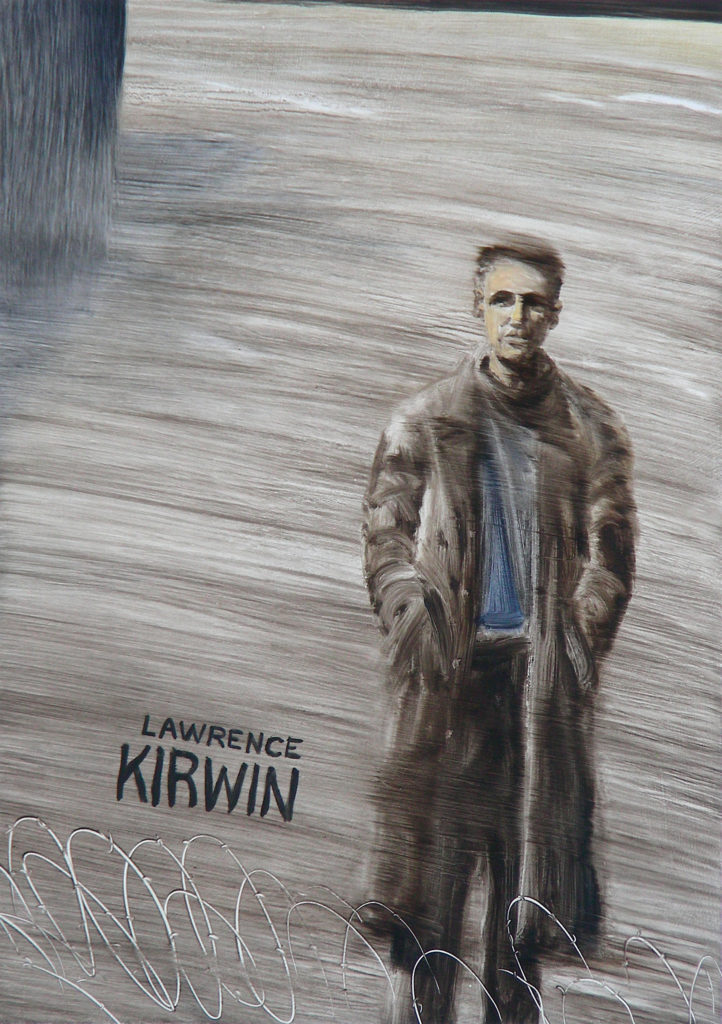

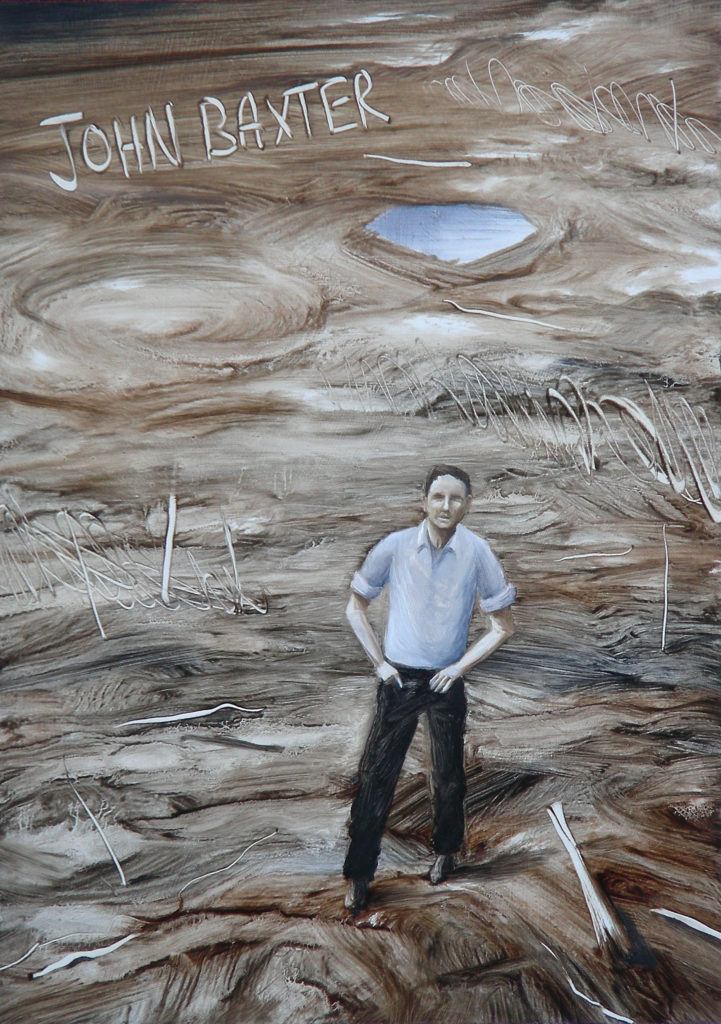

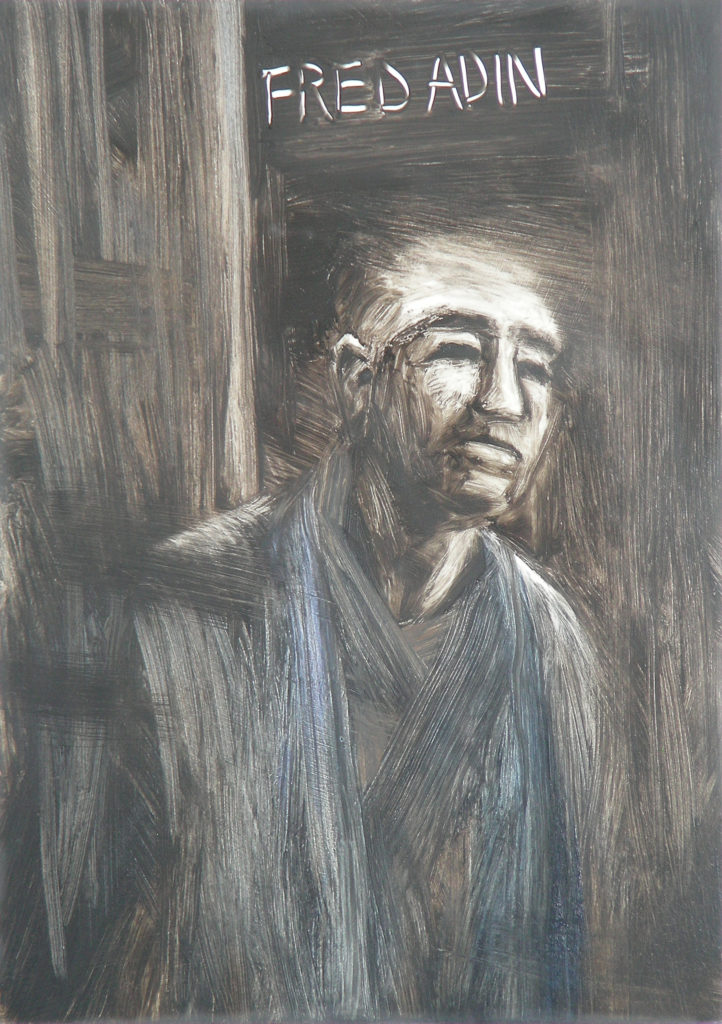

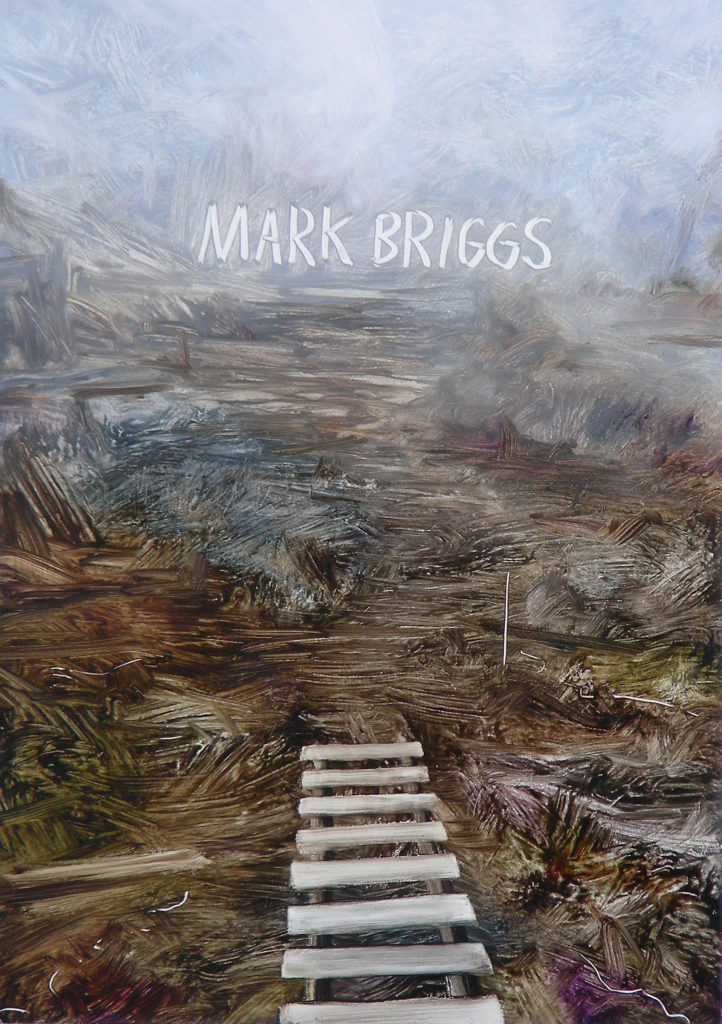

One morning in in July 1917 Mark Briggs, Archibald Baxter and twelve other objectors to military service were marched from their prison cells to the Wellington wharves and up the gangplank of the troop ship Waitemata. They were transported to England and then to the frontline in France. There they were beaten, jailed, starved and threatened with death by firing squad in an attempt to persuade them to put on the kings uniform and become soldiers. Mark Briggs, Archibald Baxter and Lawrence Kirwan were administered Number One Field Punishment. They were tied to a post in the open with their hands bound tightly behind their backs.

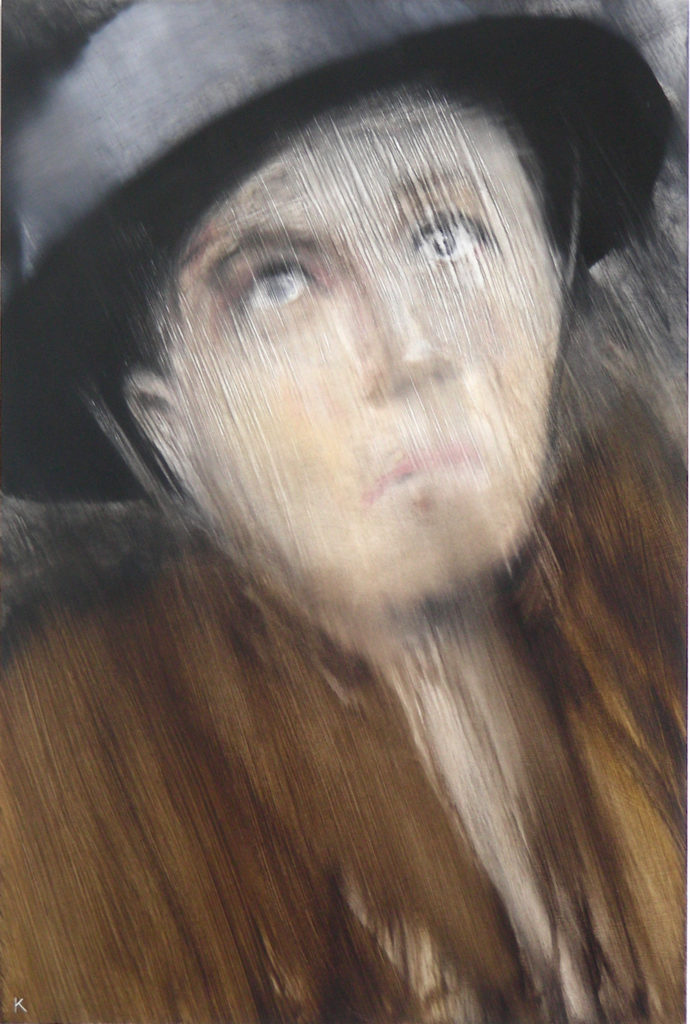

“The sergeant was an expert at his job,” Baxter wrote in We Will Not Cease, “He knew how to pull and strain the ropes until they cut into the flesh and completely stopped the circulation. When I was taken off my hands were black with congested blood… the slope of the pole bought me into a hanging position causing a large part of my weight to come on my arms and I could get no proper grip with my feet on the ground….”

“The following morning I was getting ready to go into the sale yards. My horse was feeding in the yard outside and I was in my shirtsleeves washing my face when the policeman appeared at the door. “Just something to do with these statistics Archie. Come down here out of the wind.”

As we came near the hedge another policeman sprang out from behind it and they seized me. “Your under arrest!”

Mark Briggs refused to board the troop transport Waitemata quietly and as he was forced up the gangplank. He called out to some wharf labourers to alert them to what was happening. On board he was regarded as the leader of the fourteen objectors.

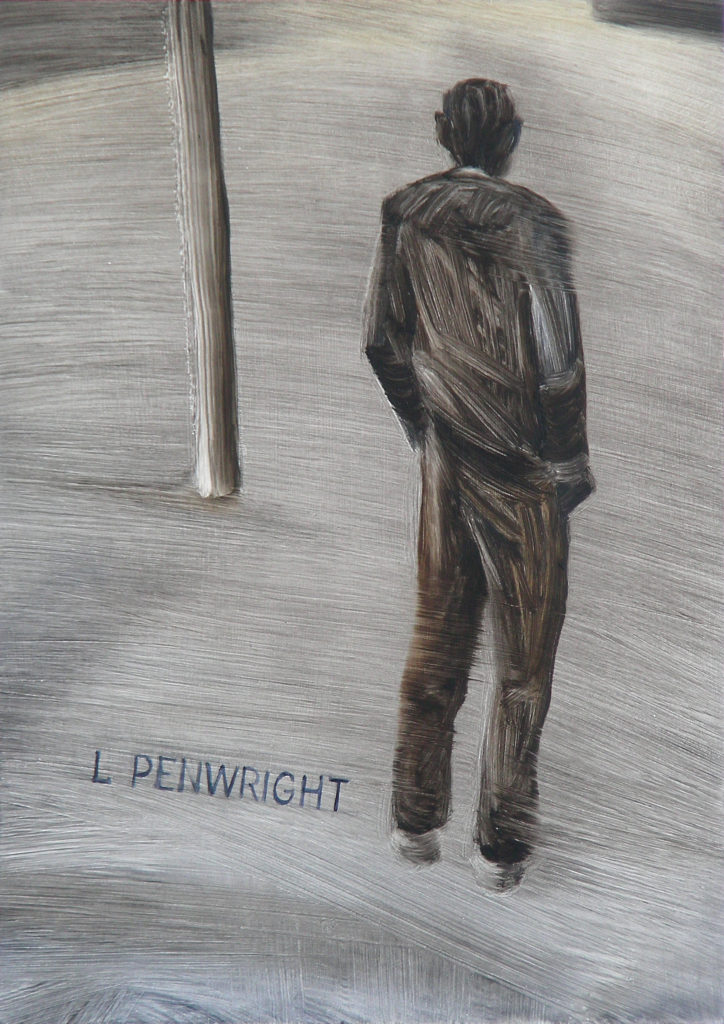

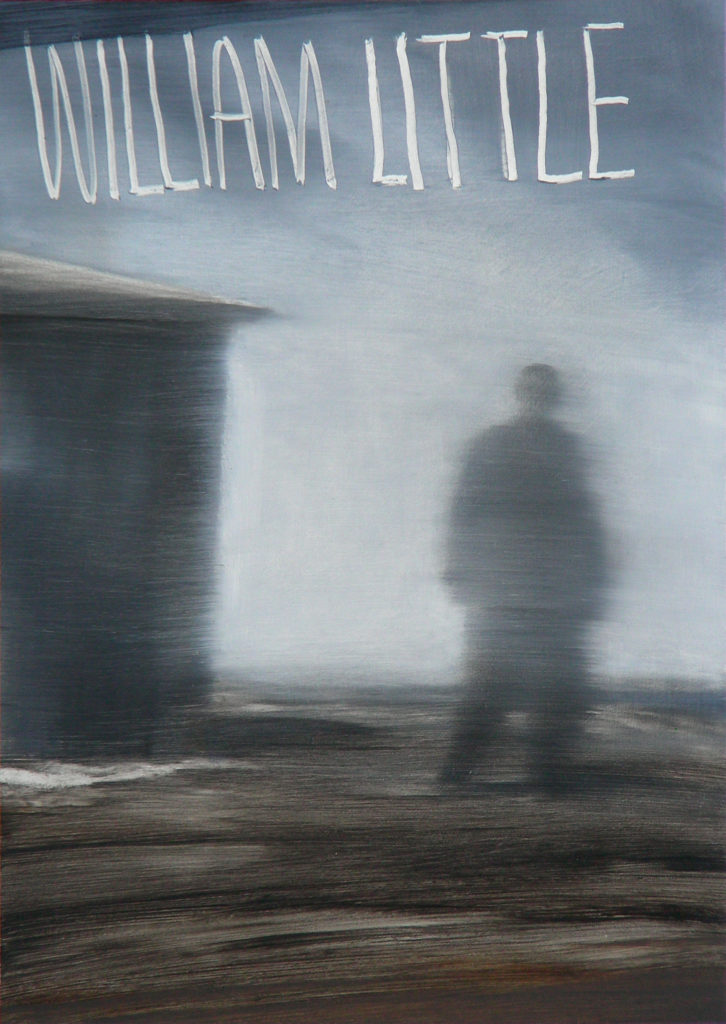

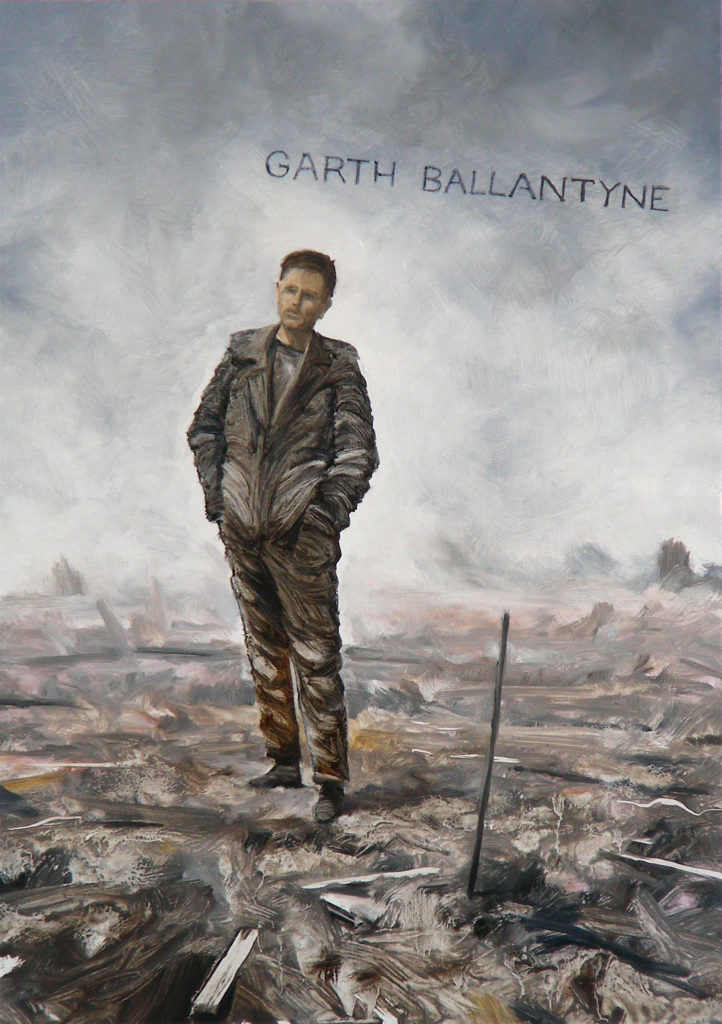

The fourteen objectors to military service secretly transported by troopship to England and then to the frontline in France where they were pressured to bear arms.

“He struck me on the mouth and ordered me again. I refused and he struck me under the jaw making my mouth bleed. He kept saying ‘Do it, Do it,” and I kept saying, ‘No.’

“I remember one day a padre addressing the troops. As we listened to him I heard the men around me sigh and murmur beneath their breath. The padre seemed out of touch with his audience and not very sure of himself. He told us that wonderful things would come out of the war, that when it was over we would be free to build a new and better world. Great spiritual blessings would spring from these times of trouble and sacrifice.”

“Here’s a man just back from France.” They said, “He’s one of the best men we have. He’s been through the whole thing and can tell you about it.”

As he came out they asked him, “How did you get on?”

“The only difference between us is that he has known from the start what it’s taken me three years to learn.”

“I remember always the gentleness and humanity of the ordinary soldiers who were close to me in those times.”

Baxter’s worst day was when a blizzard raged and even he expected not to be tied up. He was mistaken; the sergeant was determined to break him and Kirwan. The temperature fell below zero. “The cold was so intense a deadly numbness crept up till it reached my heart and I felt that every breath would be my last…”

Mark Briggs was dragged along the duckwalk in an effort to make him put on the uniform. This is how he described it in Harry Holland’s book Armageddon or Calvary.

“Along this track – as far as I could judge a distance of about a mile – I was dragged on my back. In the process the buttons were torn off my clothes, which were dragged away and consequently my back was next to the duck walk. The result was that I sustained a huge flesh wound about a foot long and nine inches wide on the right back hip and thigh. The track crossed the edge of an old shell crater which was full of water, and when the soldiers reached it they stopped. …He immediately threw me into the shell hole and dragged me through the water… when they got me out to the bank on the other side they just picked me up by the shoulders and tipped me over backwards into the water…. The MP said, “drown yourself now you bastard if you want to die for your cause. You haven’t got your Paddy Webbs and your Bob Semples to look after you now.’

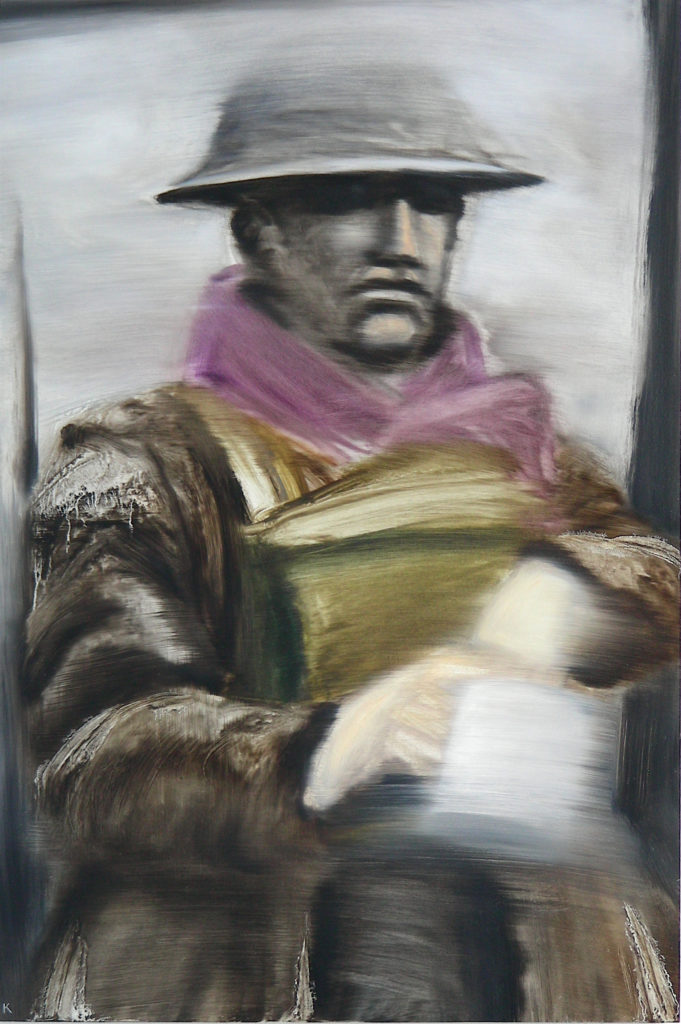

In the book Field Punishment Number One, which is illustrated with these paintings, the author David Grant says, “It is time to reflect on what their lives meant for New Zealand. They were our countries first successful dissenters.” He argues that they were at the beginning of our evolution from a conservative, insecure, bellicose, dependent, and martial country to a humanitarian, principled, independent one.

These paintings were first shown at Milford Galleries Dunedin in 2009. A later version of the show at the Tauranga Art Gallery included a new work called A Long Row of Stout High Poles. Viewers were invited to walk along the wooden duckwalk to view this painting. The text running along the top of the seven panels is a quote from Baxter’s book We Will Not Cease. It reads: “Walking along the duckwalk from the gate I observed a long row of stout high poles. These poles were for the infliction of number one field punishment.”

Musician Andrew Laking composed a sound-scape to accompany this work. You can hear this and see Ahmad Habash’s animation in this work that was commissioned by the Wellington Museum in 2017.