On a Sunday afternoon in December 1916 Tim Armstrong, a wharf labourer, spoke at a public meeting in Victoria Square in Christchurch. “Let the kings and Kaisers go and murder one another if they like but the working class have no quarrel one country with another.” Tim told the crowd, and he urged them to oppose conscription into the army. He was arrested for sedition and sentenced to twelve months in Lyttelton Jail. The quotations under each of these paintings are from a letter he wrote to his children from his prison cell.

“My dear children, As I sit alone here in my prison cell, thinking of you all and wondering how you are getting on, I thought I would write to you and explain just why I am here, in order that you may judge for yourselves weather I deserve the treatment I am getting. Perhaps I could not put you in a better position to understand than by writing you a brief story of my life.”

“I was born in a small village called Bulls in the North Island in 1875. There were nine of us in the family and we had no father to help keep the home as far back as I can remember. My mother had to go out to work to keep us.”

“Before I was twelve years of age I had left school altogether and had only passed the second standard. I then went to work in a flax mill about twenty miles from home.”

“I worked in the flax milling industry till I was about sixteen years old and used to leave one mill and go to another whenever I got a chance of higher wages.”

“I started out on a Saturday morning and about midday caught up with a man who was also carrying a swag and going in the same direction. We started talking and both found we were bound for Palmerston North. We talked of course of our financial positions. He told me he had two shillings and insisted on me taking half.”

“When I was sixteen years of age most of the flax mills were closed on account of a fall in the price and I had to look for work in some other line of business. The next place I struck was a place called Hunterville where I got work from a railway construction contractor.”

“I was working at a place called Raetihi in the king country when a boom broke out in gold mining in the Auckland province, and of course being all there for an adventure, thought that would be just the place for me. So along with a few other mates made up our minds to roll up our swags and walk to the gold fields.”

“We walked the whole way a distance of about three hundred and fifty miles.“

“It was a wonderful trip through the hot lakes districts of Tokaanu, Taupo and Rotorua. On most places on our trip we had to get food from the Maoris and sleep out in the open air but it was lovely weather and we did not mind sleeping out. We went through some places where the Maoris could not speak a word of English and we could not speak Maori very fluently. It was the fun of the world at times.”

“We arrived at Waihi and found the gold fields not what we expected and as usual had to look for someone to give us a job.”

“I only stayed a short time at Waihi… and then shifted on to the Golden Cross mine where I lived for about five years and which turned out to be the most important time in my life. I took an interest here in the affairs of the union and was soon an executive officer and before I was twenty-one years of age I was chairman of the union.”

“In February 1909 we found it necessary to leave Waihi as the employers had blocked me in every way from getting employment. We did not like the idea of leaving as I was proud of the positions I held there, however as we could not live on air were obliged to move on. We had managed to get a nice little home in Waihi and it was just about paid off so you will understand it was mighty hard to have to sell it and our furniture at half price and leave.”

“I went to Greymouth on the West Coast and I got work on the Coal Creek railway line. Your mother with you children joined me there and we went to live in Runanga. Very soon after arriving on the West Coast I was elected President of the West Coast Workers Union. So you see they got me into harness again right away.”

“Dear children you will have the opportunity to read the speech alleged to have been seditious, and I will leave it to you to judge whether I did wrong in making the statements.” In 1922 Tim Armstrong was elected to Parliament. As minister of Labour in 1935 Armstrong promoted the swift improvement in pay and conditions for the country’s numerous relief workers and legislated for the 40-hour week and the statutory minimum wage. In his maiden speech he said, “Mr. speaker, this is not the first of his majesty’s institutions of which I have been a member.”

Here is TJ McNamara’s review from the New Zealand Herald.

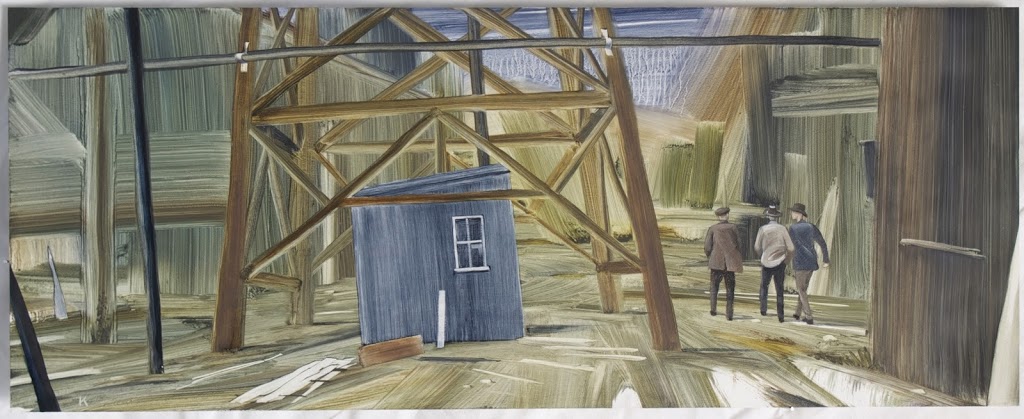

Bob Kerr, at Whitespace, grounds his painting in a text, from letters written by Tim Armstrong, then a wharf labourer, to his children from Lyttelton jail. He had been given a year in prison for sedition because he opposed conscription during World War I.

He became prominent in union activity at an early age and later was a much-respected MP. He describes his life as a young man leaving school at 12, working in the flax industry, railway construction and the gold mines of Waihi, and walking the roads with his swag hundreds of miles between jobs. The 14 paintings in the show illustrate passages from the letters and effectively recreate the times. The show is titled It Was the Fun of the World and the only time bitterness creeps in is in the painting of Armstrong and his wife and young children leaving Waihi when he had been blocked from employment for union activity. The plainness of the painting effectively matches the text. Kerr uses a very thin paint over a hard surface with a limited palette, mainly blue and brown. It works well in describing extensive flax along a river flat or the big cliffs of a railway cutting. Clever use is made of runs of paint and resistance techniques to provide the appearance of texture. The images are straightforward: the flax and the act of cutting it, the size of a railway cutting and the tools and wagon used to hack through it, the rough roads and the vitality of young men walking them, swag on back. Illustrative painting of this kind is rare now unless linked to a book but this show effectively gives insight into a personality and history with considerable artistic skill.