The Fleming family holidayed at Rotorua during the 1930s. This was where Charles Fleming first heard the kokako sing as he cycled along a bush track on the Mamaku plateau. ‘Just before leaving the bush I heard an unknown call. A most fascinating arpeggio in a flute like clear tone – high. It was repeated and would sometimes run to two arpeggios. I spent some time trying to trace the bird which gave this call.’

Many years later in 1968 in an editorial in the Listener titled ‘Mammon on the Mamaku’ Charles Fleming warned that ‘37,000 acres of native forest are destined for conversion. In preparing the ground for pine planting native growth must be completely removed by defoliant spray, chainsaw, bulldozer and fire.’

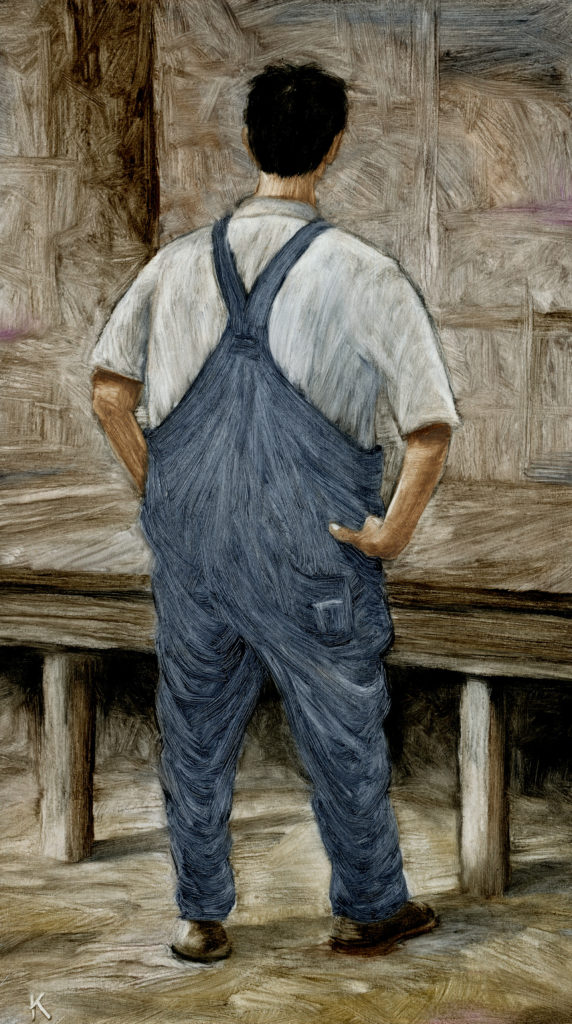

At the same time, oblivious of Fleming’s campaign. I and some school friends were exploring the Mamaku’s. We eventually came to see the destruction that Charles Fleming was warning against. These paintings are a memory of those youthful explorations. I painted them after reading Mary McEwen’s biography of her father Charles Fleming environmental patriot.

Here is a catalogue essay by the environmental writer David Young.

Kokako Calling: conservation and loss in the Mamakus – David Young

Always, the world over, the same old conservation story — that pioneering sense of

eternal abundance possessed by men who believe in making a buck out of it, while

others, usually poorly financed and with little legal support, try to hold them back. The idea that Mother Nature, bountiful to humans for so many millennia, will provide and heal and forgive yet again.

Nothing at all wrong with that? No, not when relegated to once-upon-a time. But

when harnessed to earth-shattering technologies and an ethic of Calvinistic improvement that finds its rewards in God-given company dividends, it is unsustainable. A system that even counts these things as improvement, measured by GDP, but never counts in losses to wild nature, heritage and the relationship of a people to their distinctive landscapes.

When as a youngster Charles Fleming heard kokako calling on the Mamaku Plateau the call resonated profoundly and spoke to him many years later, at a crucial time, on the cusp of modem environmentalism. It was 1968 and New Zealand Forest Products was cutting swathes through much of the little the pioneers had left of accessible nature, including some fine forests in the central North Island. Abetted by the Forest Service, vast tracts of native timber were being felled, milled and fired for transformation into pine forests.

The post-war growth was still trending up, good timber was in great demand –although native was never sold at anything other than subsidy-dampened prices. The Tongariro Power Development was under survey but was yet to thwart and manipulate flows in the North Island pumice land, the Manapouri scheme was still four years away from protective legislation that had taken about 13 years of campaigning to save the lake from being flooded by impoundment.

It was at this time that one of the nation’s most eminent and brilliant scientists, Dr

Charles Fleming, who made a name for himself in three disciplines (and would go on to achieve in a fourth) at a time when most contented themselves with just one, went back to the Mamaku Plateau to see for himself what was happening.

He immediately identified the Forest Service game plan. It was to flatten forests, milling them and replanting in pine, with fringes of native along roads to humour the casual viewing eye. Independent of means and disposition, possessed of a merciless conscience, Fleming decided that he would speak out as a public servant, in the pages of the New Zealand Listener Editor Alex McLeod, fiercely independent, was already a scourge of governments. Fleming’s outspokenness was rare, it was courageous and while mentors of his like Herbert Guthrie-Smith had said similar things before, it made him unpopular in forestry and business circles. He should toe the line he was, after all, part of the establishment, wasn’t he?

In reading his words that follow, remember that these were remnant forests, most of which had already been destroyed over the eight years:

“State forests of the Mamaku Plateau, flanking the highway to Rotorua from the north, have produced rimu and other timber over the years but have remained the most accessible place in the North Island to see native birds robin, tit, rifleman, whitehead, tui, bellbird, pigeon, parakeet, kaka and the rare kokako if one is lucky Now, screened from the highway by a pathetic hedge of tawa bush too narrow for permanence and inadequate as bird habitat — 37,000 acres [15,000ha] of native forest are destined for conversion. In preparing the round for pine planting, native growth must be completely removed by defoliant spray, chainsaw, bulldozer and fire. In the process thousands of native birds will die unseen as surely as if shot, and only a few kinds are likely to recolonise the new forests

“We have lived at the best time, with modem medicine and transport, able to enjoy New Zealand before it loses the flavour we love. The world, man’s environment, is being altered by human manipulation, and to form balanced judgments about our future environment we must cease being technologists and economists and become

philosophers, not afraid to look at the total picture.”

Fleming went on to predict, correctly, that the same pattern of exploitation would be followed in the forests remaining in Nelson, the Catlins and Southland. His was an early warning shot in the battle for native forests that would define much of the 1970s and 80s. The beech forests utihzat1on plan announced in 1974 for the West Coast and Southland became another, finally unsuccessful, part of that last grab.

At virtually the same time, representatives of a new generation of 16 year-old Boy Scouts came into the forest for an adventure on their bikes. Bob Kerr was a Scots engineer’s son from the brand new Forest Products town of Tokoroa. With mates Tub Clark and Michael Grayburn he was acquainting himself with the Mamakus, a bit of wildness so different from the unending radiata pine glimpsed through the waisted curtains of his mother’s kitchen window

The boys were attracted by the tramline and its tunnel and the diesel tractors towing their trains of tawa logs back to the Bartholomew Timber Company’s mill in the village of Te Whetu. “Near the end of the tramline, over a wooden trestle bridge in the regrowing native scrub we found a collection of timber-workers’ huts and camped in one overnight,” he says.

“The houses had sash windows and corrugated iron chimneys. Our log book records that we spent Tub’s sixty cents in the Te Whetu General Store, stocking up on luxuries.”

Bob Kerr’s log also records their pleasure in hearing shining cuckoo and wood pigeon in the forest. However they had a boys’ fascination for machinery and the infrastructure of muscular production.

Reared on utopian promises of industnal progress, the verities of growth and the vagaries of their parents’ Depression, the young Kerr cycled his ambiguities through the doomed forest.

“Later that year we went back.” Their sense of loss was not only of forest, however, but of built heritage. “The trestle bridge had been collapsed into the creek, all but one of the huts had been bulldozed and poking through the black ash of the burnt over native regrowth were regular rows of small dark green pine seedlings,” says Bob.

“It didn’t look very nice to us but we had no idea of the battle being fought by Charles Flemmg over the Forest Products lease of large areas of the plateau and the proposed destruction of the native forest.”

The paintings in this show certainly commemorate Charles Fleming’s staunch environmental patriotism. “But they also record delight in that Boys’ Own model railroad and an imagining of those who worked on the line”, Bob says, “And in the mill where the saws were so noisy that the henchman, the pin boy and the tailer-outer could only communicate in hand signals.

“In the early 1970’s the entire town of Te Whetu was auctioned. One of the conditions of sale was that if you bought the school, or the general store you had to take it with you. I’m told that all that remains is the new swimming pool that was built by the education department shortly before the school closed. It is surrounded now, by tall dark green pine trees.”

David Young

This exhibition was shown at the McPherson Gallery in Auckland and the Rotorua Museum of Art and History in 2007.