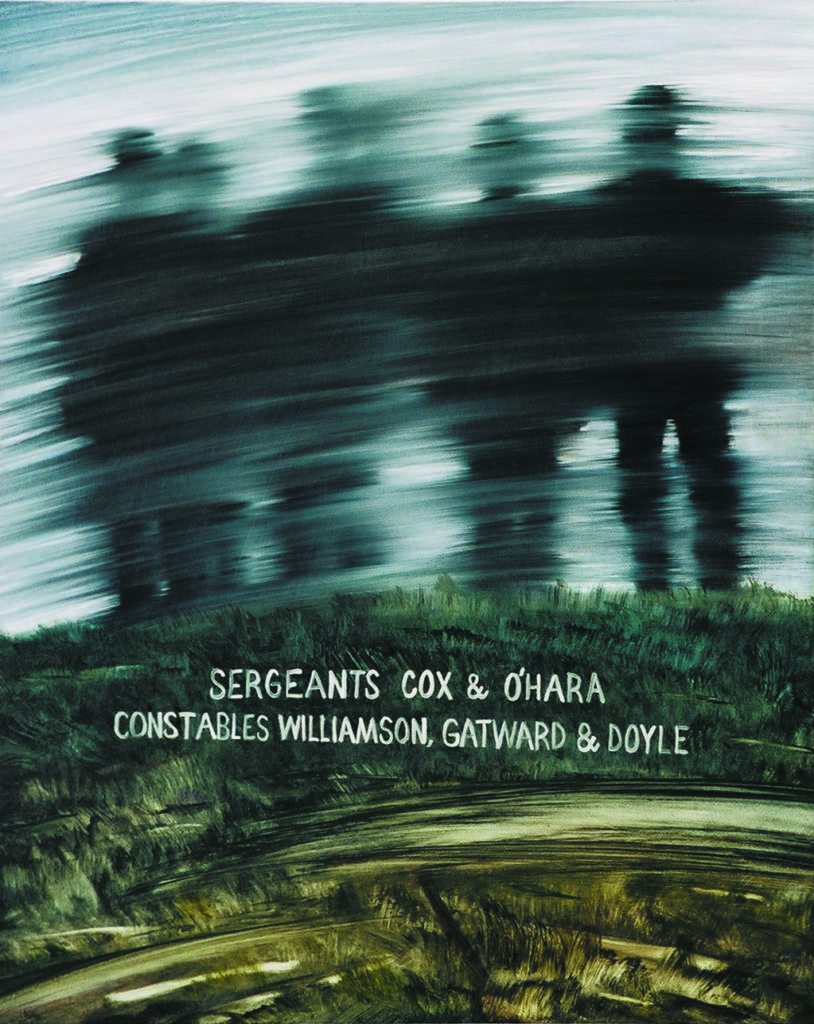

Dave Kent has just finished hanging Those who are not for carbine duty must bring their batons, handcuffs, revolver and ammunition at the Whakatane Museum and Gallery in 2003. The title for this painting comes from the instructions Police Commissioner Cullen gave to the policemen who took part in the raid on Rua Kenana’s community at Maungapohatu in 1916. It is made up of 72 panels showing those who took part in this invasion that resulted in the deaths of Rua’s son Toko and Te Maipi.

Catalogue essays by Tamati Kruger and Mark Derby.

He Kupu Rarau – Tāmati Kruger

Koinei ārātau kanohi.

These are their faces.

Ētahi o te rima tekau mā rima o te ope pirihimana i tukuna ki te patu i te kino o te mana motuhake ngākau ātete ture e puta mai ana i Maungapōhatu.

Some of the fifty five members of the police contingent assigned to quell the threat of independence and open resistance to the law emerging from Maungapōhatu.

Oti atu anō, he whakapoutiki nā rātau i te mana kāwanantanga.

Moreover, they were to aver the authority of the government.

I te Rātapu 2 o Paengawhāwhā 1916 kokiritia a Rua Kēnana ki te pā o Maupā.

On Sunday 02 April 1916 Rua Kēnana was attacked the village of Maupā invaded.Tokomaha i tū, ko Toko (tama a Tai) rāua ko Te Maipi i patua kia mate rawa.

Many were wounded, Toko [son of Rua] with Te Maipi were killed outright.

Ka mauria ngā mauhere ki Tāmaki i reira ka whakawāngia ka whiua ki te whareherehere.

Those seized were taken to Auckland and there put on trial, then imprisoned. The police force were glorified as heroes and champions; Rua and his retinue reproached as traitorous criminals.

He tino whakairi whare tuhinga tēnei nā te mea he Pākehā e whaiwhakaaro ana ki tētahi mahi kua pōhēhētia he take Māori anahe.

This is an extraordinary exhibition by the fact a Pākehā has chosen to image thoughts on a subject considered erroneously by many to be a Māori historical event.

He Pākehā, he Māori i reira. Koia nei tā te Pākehā pūmahara mō aua rā.

Both Pākehā and Māori were there. This recalls Pākehā memory of that time.

Ko ēnei tuhinga ā Bob Kerr e whaimuri ana i ngā whakaahua i tangohia i te kokiri mau pū o ngā apataki a te kāwanantanga i Maungapōhatu i te tau 1916.

These paintings by Bob Kerr are based on photographs taken to record the armed invasion of Maungapōhatu by police in 1916.

Ko ngā āhua ēnei o aua tāngata i whakanuia he tokowhare ki ētahi he rari kaipū.

Depicted are the faces of people celebrated as patriots yet vilified by others as murderers.

He mata kanohi tahu i te wareware e hou atu ai te matatau whakarere mataku.

Faces persuading us not to turn away from ourselves so we may understand more and be fearless.

Tēnā koe Bob, e mihi ana ki te ringawero kei roto i a koe.

Tāmati Kruger – Tūhoe Artist 23 Koopū 2003

Contested Landscape – Mark Derby

Rua Kenana’s religious community at Maungapohatu, claimed the newspapers in early 1916, “is pretty well supplied with rifles and ammunition obtained from Assyrian hawkers who … smuggled them into the Urewera Country under their fancy goods and cloths.” Some said Maungapohatu was defended with a machine gun. These rumours proved unfounded, but they helped to justify the police invasion which followed. While Bob Kerr was painting the pictures in this exhibition, the news on his radio was describing the progress of a war in Iraq, justified by unfounded claims of monstrous weaponry.

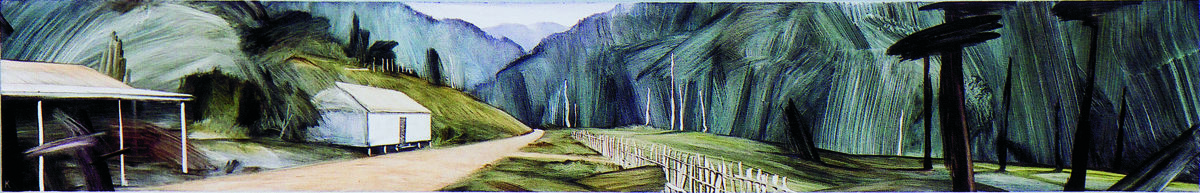

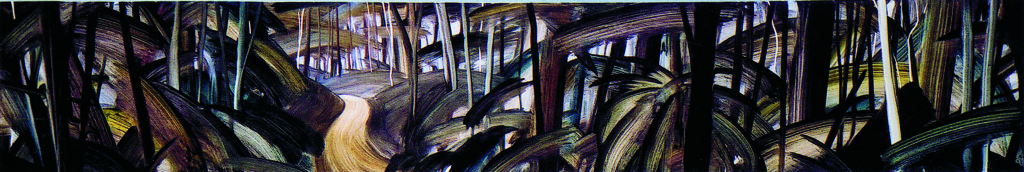

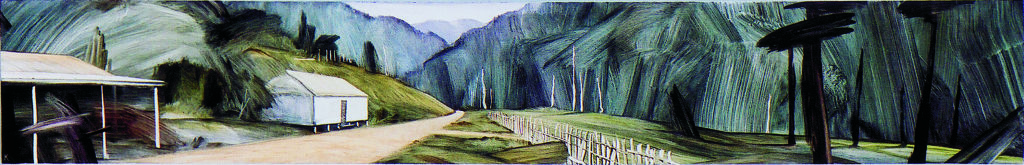

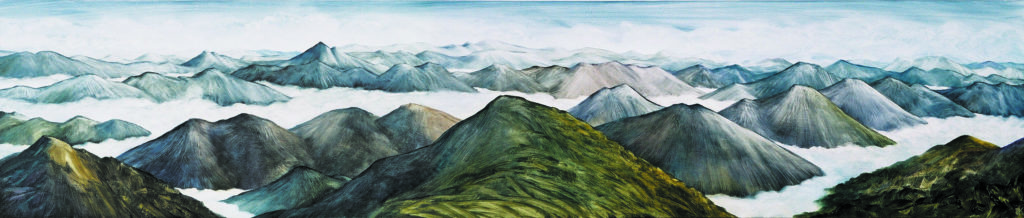

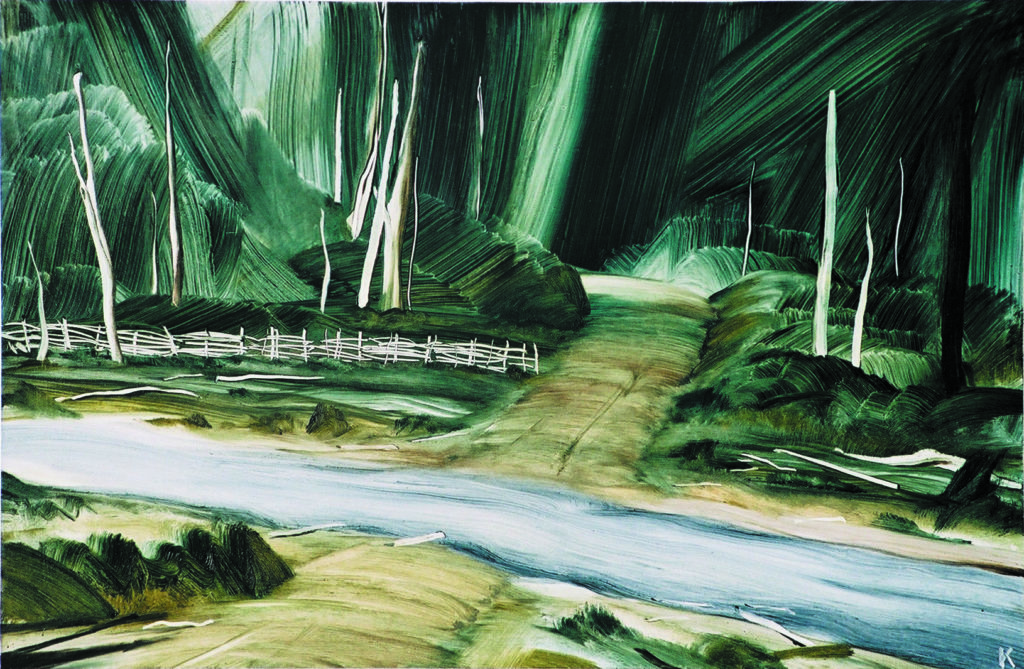

This exhibition is the most recent step in Bob’s ongoing project to paint the contested New Zealand landscape, the sites of uncomfortable moments in our post-colonial history. As in his earlier exhibitions, these paintings draw on incidents, writings and photographic images from New Zealand’s past to uncover the tensions which still lie beneath the surface of many apparently tranquil vistas.

In this case the landscape is the Urewera, especially the route towards Maungapohatu, in the heart of Tuhoe territory, taken by a large party of police in 1916. As Tamati Kruger indicates above, this fatal expedition was a misguided and unnecessary collision between two utterly different societies, one heavily armed, the other nearly defenceless. The resulting tragedy remains vivid to the people of Maungapohatu and their descendants. The Waitangi Tribunal is about to hear evidence on claims in the Urewera, and the 1916 police raid will figure strongly.

The starting point for many of these paintings was the series

of remarkable photographs of the police raid taken by a prominent Auckland press photographer named Arthur Breckon. Although the police expedition was planned and carried out in secrecy, Breckon and a reporter named John Birch were invited along to cover the police actions. In effect they were ‘embedded journalists’, like those who reported one side of the Iraq War. Their combined account of the three-day march to Maungapohatu, and the bloody gun battle which took place there, appeared in major newspapers around the country.

At that time the whole country was caught up in a devastating European war. The role of the two journalists was to portray the local conflict in the Urewera as the heroic defeat of a dangerous dissident. This was the only version of the expedition which most New Zealanders ever received.

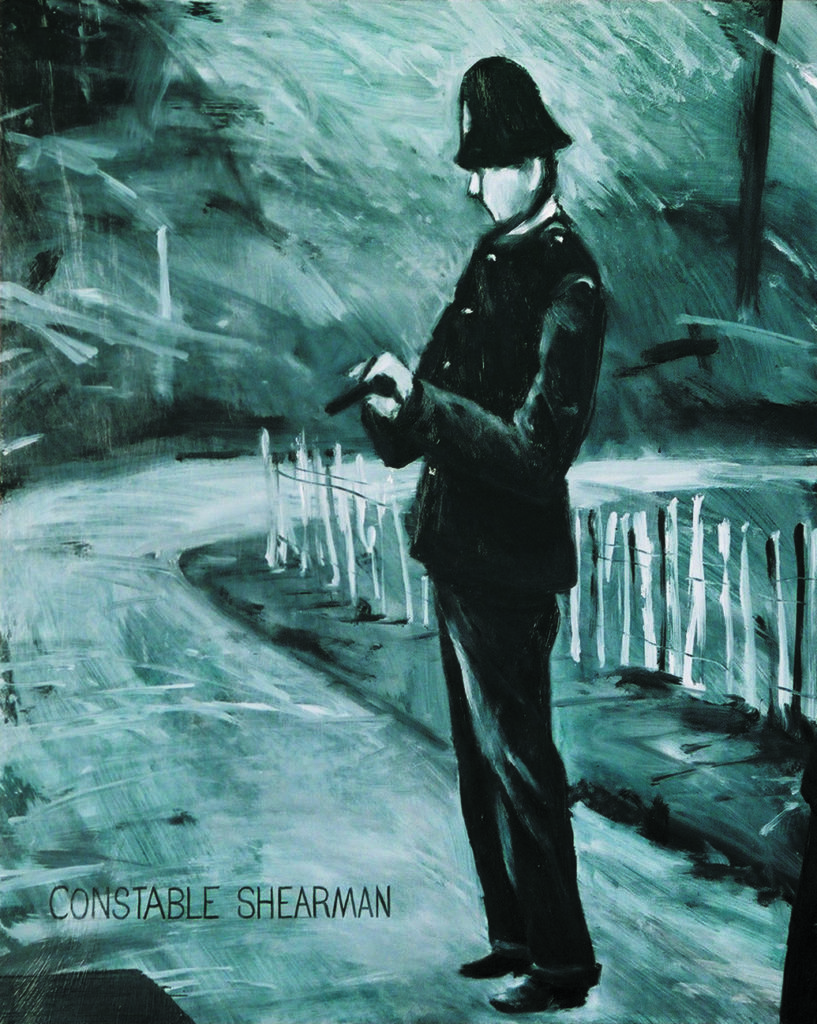

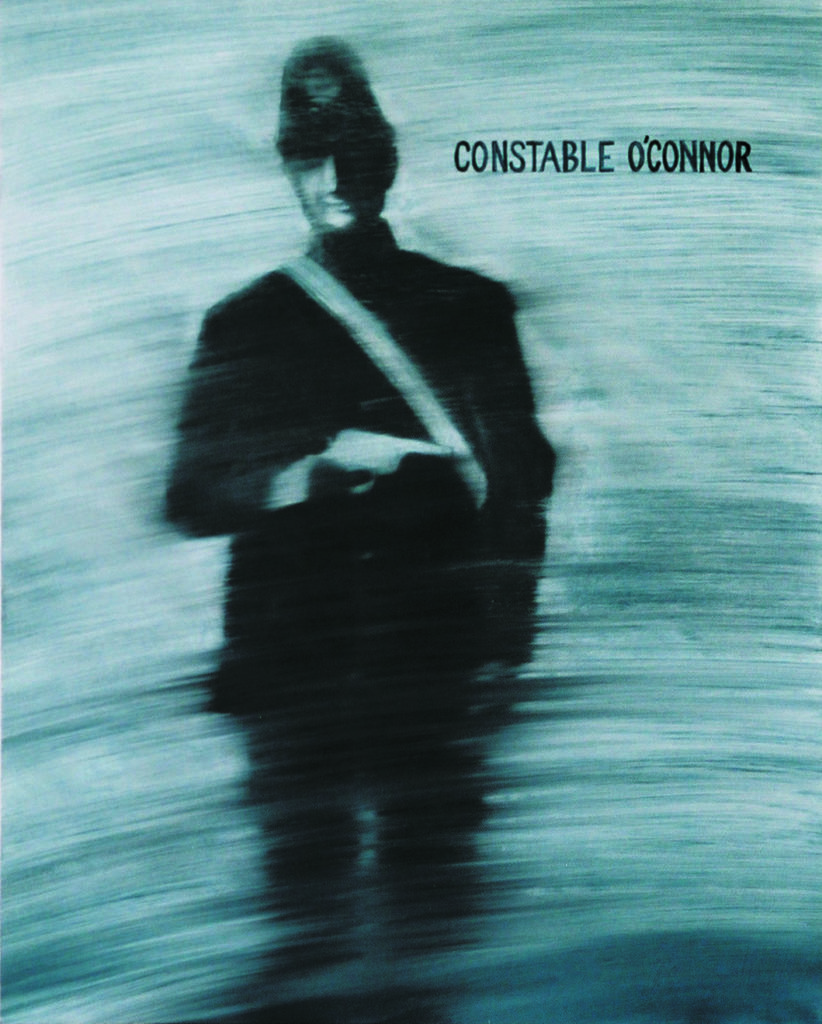

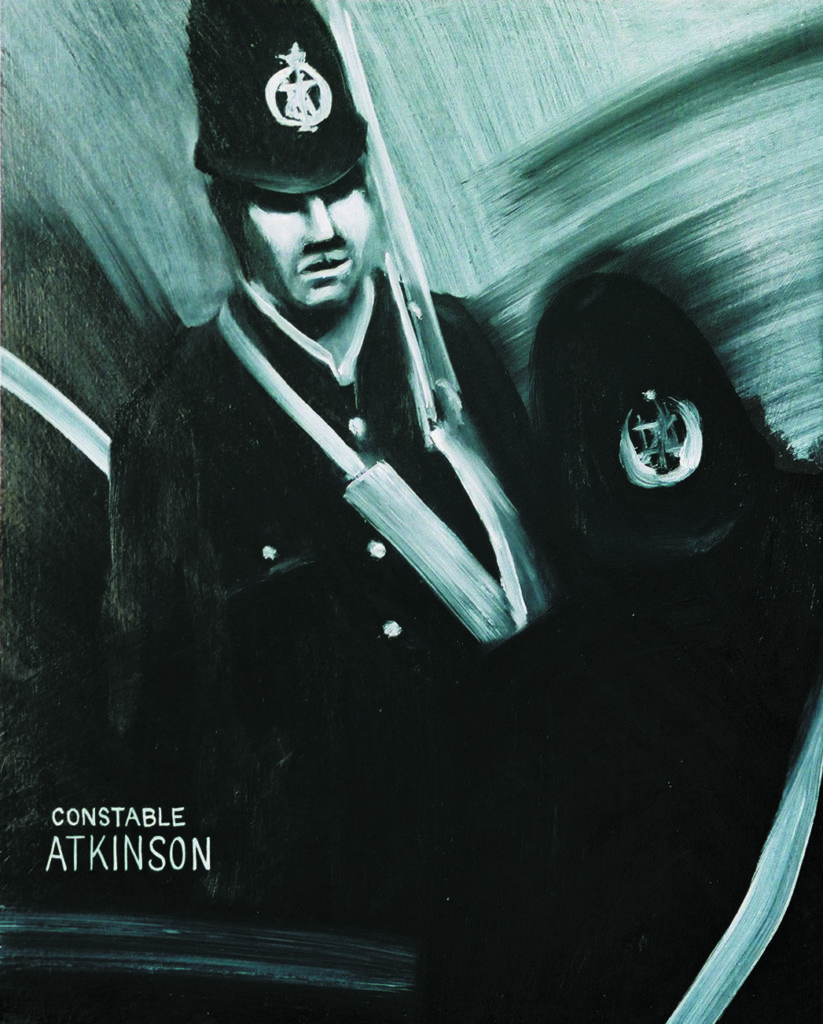

This exhibition re-examines Breckon’s photographs from a present-day and very different perspective. The major work in the show, made up of 72 panels showing each of the police officers who took part in the raid, is named from the instructions Police Commissioner Cullen gave to those men

– “Those who are not for carbine duty must bring their batons, handcuffs, revolver and ammunition”.

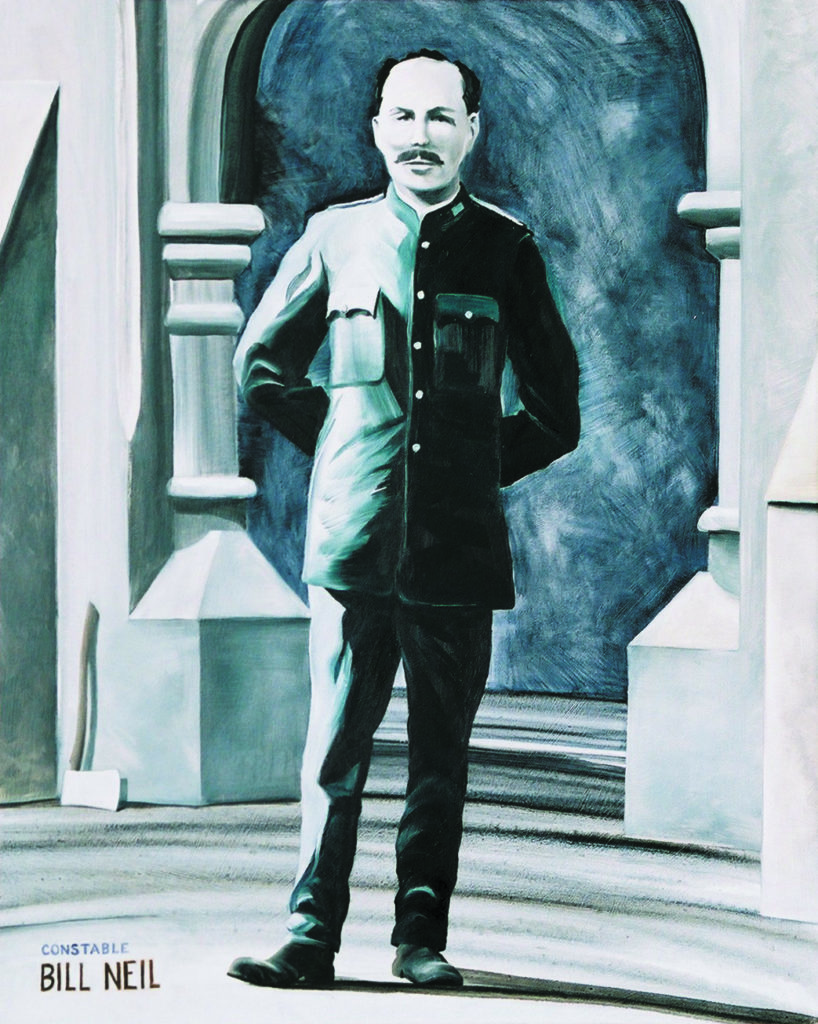

While many of the policemen in this work, like the unfortunate young Irish constable John Neil, are clearly portrayed and identifiable, others, like Constable McIntyre, are shadowy suggestions. Bob is not making a police-style identikit of the men who marched on Maungapohatu, but is instead using Breckon’s photographs as a starting point to evoke the spirit of that terrible misadventure – its bravado, its military character, its painstaking organisation, its huge scale.

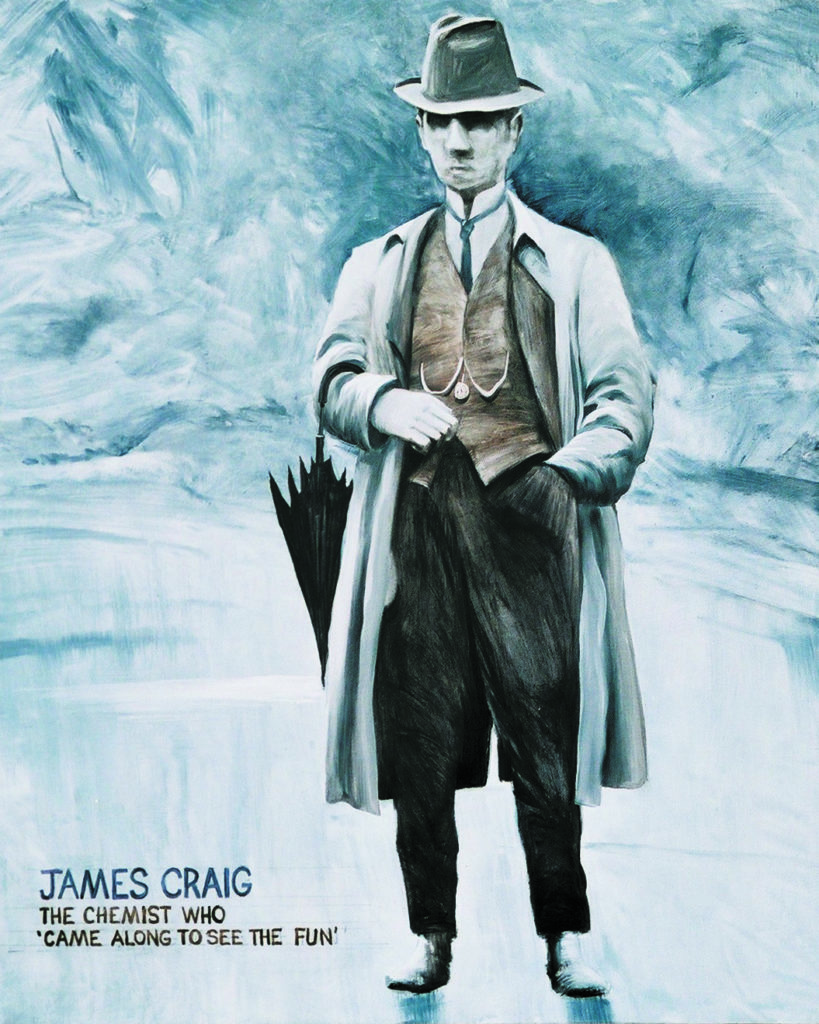

Another painting uses the words of the reporter John Birch, who noted that the police, as they sweated up the rutted trail to Maungapohatu, had their minds not only on their immediate objective but also on its possible outcome – “What valuable land there is tied up, and in Maori hands, in this Urewera country”. Large areas of this valuable land passed out of Maori hands after the police raid, as Rua and his people were forced to pay for the entire cost of the expedition, along with legal costs, medical bills and fines.

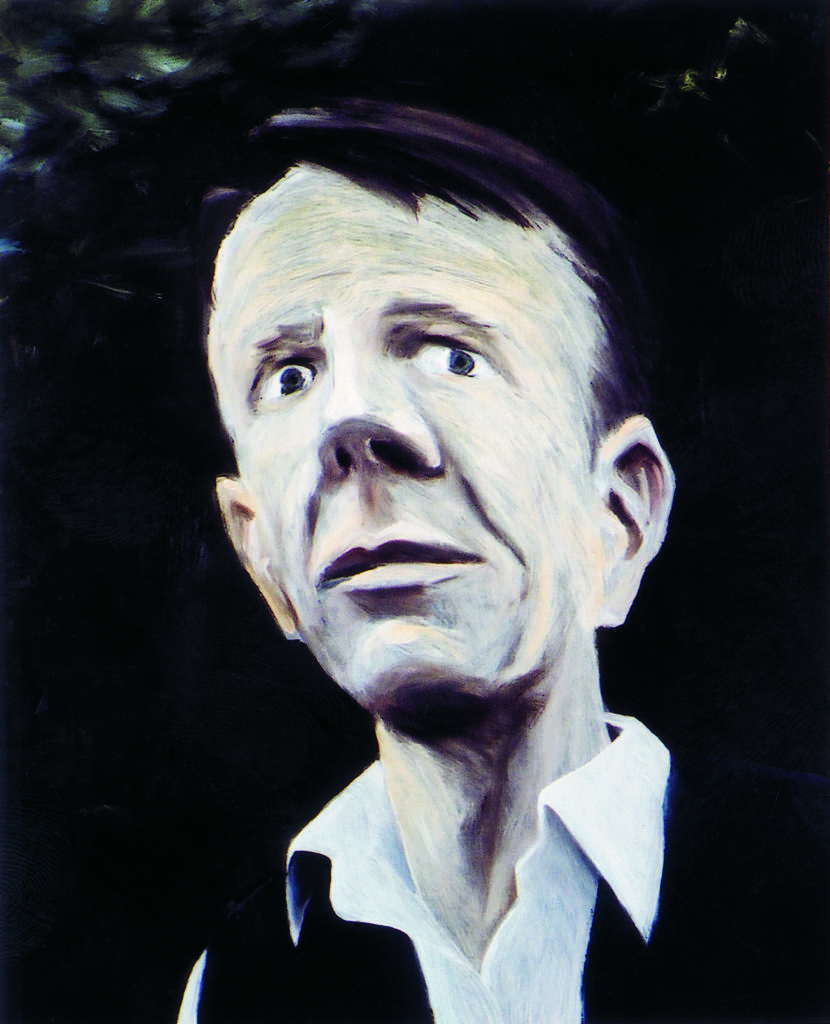

One member of the Rua expedition has a painting to himself. The man who organised the raid and personally headed the main police party was the Police Commissioner, John Cullen. In 1916 Cullen was almost at the end of a career noted for ruthlessness and an apparent readiness to disregard the law whenever he considered it necessary. His tactics for ending the Waihi strike in 1912 resulted in the death of a striker, and gave him a notorious name among working people. Many people hold Cullen directly responsible for the two deaths and several injuries which occurred at Maungapohatu. This powerful and uncompromising figure has featured before in Bob Kerr’s work and is likely to appear again in his next exhibition, which will deal with the landscape and history of Tongariro National Park. Cullen spent his last years as a voluntary ranger in the park, and introduced the heather which has since become a destructive noxious weed.

When Bob Kerr studied painting in the 1970s, his most influential teacher was Colin McCahon, who has also painted the history and landscape of the Urewera. Bob’s approach is more narrative. In this exhibition his perspective is on the role of the police in the events of 1916. In re-examining the images they made of themselves almost ninety years ago, he finds nothing to glorify but much to remember.

November 2004

Mark Derby is a Wellington writer He written a biography of Police Commissioner John Cullen and was a co-director with Dave Kent of Idiom Studio where these paintings were first exhibited.